One of the less widely known consequences of ISIS’ devastating rise is in northern Iraq is the existential threat it has unleashed against the Assyrian people, writes Mardean Isaac.

ISIS took over Mosul on 10 June 2014. By August, the Nineveh Plains — one of the heartlands of Assyrian continuity — was emptied of its inhabitants. Around 200,000 Christians, most of them ethnic Assyrians, were forced to abandon their homes and property following the last minute withdrawal of the Kurdish Peshmerga that had pledged to protect the area and the subsequent ISIS incursion. So abrupt were these civilian flights, and so exigent were the demands of the extremists, that passports, pension books, and even jewellery on the person of those fleeing were confiscated.

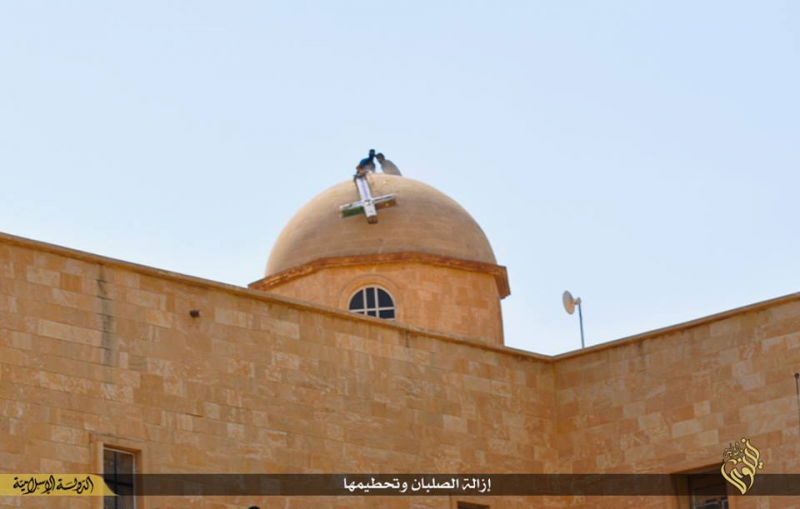

The 45 Christian establishments in Mosul, along with abandoned homes, were almost immediately converted into usage by the group. Priceless manuscripts held in churches, monasteries and libraries — such as the Mor Behnam monastery — were looted and destroyed. A campaign of cultural vandalism waged against Assyrian heritage by ISIS militants has included the destruction of the ancient Assyrian cities of Nimrud and Khorsabad, amidst the selling off of ancient Assyrian heritage to fuel the Islamic State’s expansion. Assyrian and Christian histories are inextricable in Iraq: the aforementioned Mar Behnam monastery, built in the 4th century atop the tomb of Behnam and his sister Sarah, the offspring of the last pagan Assyrian king, attests to this. This crucible of the earliest civilisations, cultures, and languages is being uprooted and transformed permanently.

Assyrians are one of the three indigenous peoples of Iraq, along with Mandaeans and Yezidis. Since the fall of their ancient empire, the Assyrian people have maintained themselves as a discrete ethnic community, navigating their existence under the Persian, Arab, and Ottoman empires. The modern Assyrian language is rooted in Akkadian and Aramaic, the original languages of what is now northern Iraq. Since the advent of Christianity, Assyrians have been the cultivators and preservers of the Syriac Christian heritage, some of the profound cultural achievements of which include the translation and transmission of classical Greek texts into Arabic during the Abbasid period. Assyrians traditionally belong to Syriac churches including Syriac Orthodox, Chaldean Catholic, and Church of the East confessions.

Since the invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the subsequent collapse of the Iraqi state, Assyrians have been exposed to seemingly unlimited gangsterism, violence, and atrocity. Seventy-eight churches have been bombed across the country since 2003. Kidnappings of both clergy and laypeople are routine. Entire neighbourhoods in Baghdad, such as Dora — which housed 150,000 mainly Assyrian Christians on the eve of the invasion — are now bereft of their Assyrian population. The number of Assyrians in Iraq has dwindled from over a million on the eve of the war to around 300,000 today. The Assyrian population of Syria has also been the target of atrocities: hundreds of Assyrian civilians remain in ISIS captivity. The numerous crises following the fall of Saddam all contributed to this disproportionate ruin wrought on Assyrians and other minorities: the power struggles, the collapse of the army, the absence of stable institutions, corruption, sectarianism and revanchism in the political elite.

And it is the persistence of these and other crises that has led to the startline inaction in the face of ISIS. The speed and scale of the collapse of Assyrian life in the face of the group have been matched only by regional and international torpor in response to it. The Peshmerga-ISIS line — just above the Assyrian town of Batnaya — has remained unchanged since September. The prospect of raising a combined force to combat the group in northern Iraq has been plagued by intense suspicion between and within the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and the central government and their various political constituents.

Emigration outside of Iraq is constant. Noor Matti, who runs the Shlama Foundation, a humanitarian organisation based in Erbil, estimates that at least a third of Assyrians displaced from the Nineveh Plains and around a tenth of the 120,000 Assyrians already living under the KRG have left the country over the past year. This relentless flight is catastrophic on at least two levels. Those displaced persons with the least means often encounter peril on their path to asylum limbo in the west via Jordan or Turkey: these Assyrians, who usually lived pastoral or simple lives in the Nineveh Plains, leave Iraq out of desperation. The draining of their numbers severely damages the prospect of repopulating the Nineveh Plains. The departure of those professional Assyrian families who live secure lives in Erbil or Dohuk is draining the community of leaders, the highly educated, and promising young people.

Significant humanitarian aid and investment are needed to uplift the Assyrian communities of northern Iraq. In particular, there is an urgent need for the construction of homes in areas where Assyrians are concentrated in order to allow displaced Assyrians to establish themselves and rebuild their lives. It is imperative that these efforts are directly channelled through established, local, Assyrian-led civil society, aid and developments organisations. These groups are deeply rooted in the region, and supple enough in their capacities and activities to remain close to the needs of people and communities.

More broadly, in the continuing absence of the international protection of the sort afforded to Iraqi Kurds in the face of genocide, the international community must do more to support independently led Assyrian security and governance. The long-vaunted need for locally derived security forces comprised of Assyrians and Yezidis was made even clearer when Iraqi and Iraqi Kurdish forces absconded from the Nineveh Plains and Sinjar. Assyrian-led security forces, which have been in development for several months, must be buttressed so they can defend their communities and assist in the repopulation of empty Assyrian land, and Assyrians require greater powers of administration in areas in which they have a strong presence. These measures would go some way to restoring lost dignity, and would empower the Assyrian people to steer their fate away from decimation and, in time, towards flourishing once more.

Source: AINA.ORG