Native-born Christians in the Holy Land now constitute only 2 percent of the region’s population, their numbers diminished by a continuing emigration. Who are the Holy Land’s Christians? How do they express their reasons for leaving or staying? What is their perspective on the region’s plight? Strong viewpoints on those questions by two Palestinian Christians — one who left the Holy Land and one who remains — are presented here. George Ghattas studied at Bethlehem University and Holy Ghost College in Dublin, Ireland. He is chairman of the local committee of the Holy Land Christian Ecumenical Foundation and head of programs development for the Latin-rite Patriarchate in Jerusalem. Nadim Haddad was born in Ramle, Palestine, in 1943. His family took refuge in Jordan in 1948. Educated in Catholic schools in Amman, he came to the United States in 1961. He lives in suburban Washington, working in the aerospace industry.

Native-born Christians in the Holy Land now constitute only 2 percent of the region’s population, their numbers diminished by a continuing emigration. Who are the Holy Land’s Christians? How do they express their reasons for leaving or staying? What is their perspective on the region’s plight? Strong viewpoints on those questions by two Palestinian Christians — one who left the Holy Land and one who remains — are presented here. George Ghattas studied at Bethlehem University and Holy Ghost College in Dublin, Ireland. He is chairman of the local committee of the Holy Land Christian Ecumenical Foundation and head of programs development for the Latin-rite Patriarchate in Jerusalem. Nadim Haddad was born in Ramle, Palestine, in 1943. His family took refuge in Jordan in 1948. Educated in Catholic schools in Amman, he came to the United States in 1961. He lives in suburban Washington, working in the aerospace industry.

This Is My Home

By George Ghattas

I look at my children as they grow and ask myself what makes them different from children born anywhere else than Bethlehem. It must have been the same question my father asked when I was born.

In the 1950s and ’60s, after my father decided to leave and try his luck elsewhere, we lived outside the homeland, traveling all the way down to Latin America where my father’s sister lived. He already had lost too many things back home during and after the war in 1948, most important his freedom.

I was born into a family of 10. I still remember the fun we had growing up to become today’s fathers and mothers to Palestinian Christian children.

My father and mother decided to leave Honduras and come back to Bethlehem just before 1967’s Six-Day War. They were among the few who chose to come back. The larger majority, forced to emigrate in the first place, decided to let go of what bound them emotionally and nationally to the homeland and become patriots in places where they were and remained strangers.

The day we set foot back in Bethlehem, we renewed a binding relationship with the birthplace of my forebears and a place we never will leave.

I know that many who left back then were forced to do so. They had to leave. For it is draining to enter into a totally new way of life, a new place, to accept being a stranger. People do not leave their home unless they are forced to or are seeking greater fulfillment and a better life. The big difference between the two cases is choice.

I did not choose my parents or my religion, not even my name. I did not choose the city or the neighborhood I lived in or the school I went to. But I chose to study at Bethlehem University, to fall in love, to leave for Ireland, to work for the church, to get married, to have children, to have my own house, to live in Bethlehem.

Recently Bethlehem, my home town, was turned into a prison. The same roads, the same streets, the same house that nurtured my adulthood, my sense of direction, my identity, became the cage of my freedom. I and my small family were under curfew for more than 60 days in three months time. I definitely did not choose that.

Now it is customary that young parents and young adults, families and individuals alike, rich and poor, think of leaving. Some will act on it, some already did. The reason is that life in Bethlehem has become unbearable, risky, pressured. Of course, under such continued occupation by the Israelis, the besieging of a whole population, families become wary of the future and more often wary of their children’s future.

I share the same worry and get frustrated with all these incidents and the harsh reality that impedes our progress and growth as individuals and as society. But I love Bethlehem.

I will choose to stay in Bethlehem, my home and that of my people, in witness to my Lord, in harmony with my identity, in love for my family and in trust of a future that I am a part of and can contribute to. I will choose to stay.

I Was Forced to Leave

By Nadim F. Haddad

I left the Holy Land because I had no choice!

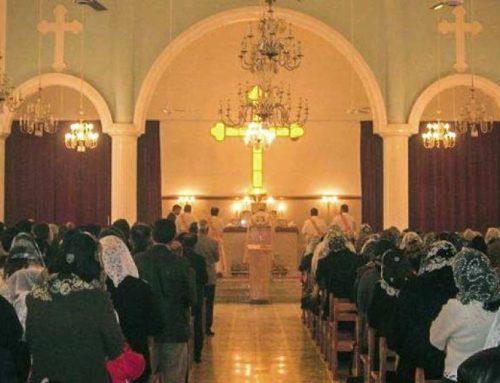

I was born in the Holy Land in 1943 to a Melkite Catholic family. The Melkites trace their history to ancient Antioch, where St. Peter organized the church before he went to Rome. That’s how far back my Christian heritage goes.

My parents settled in Ramle, an ancient Arab city in coastal Palestine. (Ramle is believed to have been the home of Joseph of Arimathea and site of the 12th-century treaty between Saladin and King Richard the Lionhearted.)

It was a troubled time. In 1917, before the British Mandate, British Foreign Minister Arthur James Balfour sent his famous (or infamous) letter to Lord Rothschild supporting a national home in Palestine for the Jewish people, “it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine.” Those communities then outnumbered Jews 12 to one.

Not long afterward, Jewish immigration escalated, and the immigrants started organizing themselves into underground military organizations. It became clear to British and native Palestinians that the “national home” was being interpreted as a Jewish state where native Palestinians would have no role. Friction escalated.

Contrary to what many believe, the Holy Land friction never was religious. Palestinians viewed Zionists as “colonialists” who came to take their country from them, and Zionists viewed the indigenous population as an “obstacle.”

On July 22, 1946, when the south wing of The King David Hotel in Jerusalem was blown up by the Irgun, a militant Jewish organization, 91 people were killed, my uncle among them. Earlier my aunt was left with severe emotional trauma when Zionist soldiers broke into their home. She didn’t live long after that episode.

We left Palestine as refugees in 1948 and never were allowed to return. Ramle was “cleansed” of its population. My father and grandfather, left behind in Palestine (my father worked in Jaffa), had to leave to rejoin the family in Jordan.

On April 9, 1948, the Irgun and others entered the Palestinian village of Deir Yaseen and massacred more than 250 unarmed villagers, then toured the streets of Jerusalem with loudspeakers promising the fate of Deir Yaseen to those who would not leave immediately. That was one of many incidences of ethnic cleansing.

On May 14, 1948, the British Mandate over Palestine ended; the next day Israel was proclaimed a state. During the previous six months, 300,000 Palestinians were driven out, with the Zionist armies illegally occupying much of the territories reserved for an Arab state by the proposed U.N. Partition Plan of 1947.

Most people of Ramle and neighboring Lydda, under orders signed by Yitzhak Rabin, were loaded on trucks and dumped across the River Jordan. These were the more fortunate ones; the less fortunate were buried in mass graves.

What do I expect for the future of the Holy Land? Not much, unless we act! For 54 years, and after a multitude of empty U.N. resolutions, the world has done nothing to remedy the injustice to the people of the Holy Land. “Ethnic cleansing” continues under the pretense of “fighting terrorists.”

Christians are down to 2 percent of the Holy Land’s population. Soon the holy places will become nothing but museums run by the Israeli Tourist Office.

END

07/09/2002 2:51 PM ET