Residents of a Palestinian Christian housing project in the West Bank village of Beit Sahour say Israel is encircling their community with a security road to separate them from a nearby Jewish settlement.

Reuters

“With this situation they will put us in a cage, a zoo,” said William Sahouri, 42, a resident and member of the project’s housing committee. “We will not be able to expand.”

The project lies close to Bethlehem, south of Jerusalem, where the Greek Orthodox Sahouri family live in a modern three-bedroom home, with two flat-screen televisions and a small bar displaying a collection of whiskies and other liquors.

While their Jewish neighbours celebrate Passover this week, they are fasting for Lent ahead of Orthodox Easter, and their house is overflowing with the delicious aroma of lentil soup.

Stepping out on the balcony of his master bedroom, Sahouri points to the Israeli security road, with electronic warning fences, that runs 30 metres (100 feet) from his apartment block. Only Israeli army vehicles can use the road, to patrol the area.

The noise of tractors and bulldozers is a constant nuisance, said Sahouri. Once completed, the road will encircle the whole area, forcing residents to enter and leave via a gate controlled by Israelis.

Beit Sahour’s fate was decided by an Israeli military order issued on April 29, 2003, by Moshe Kaplinsky, then-chief of the army’s Central Command that includes Judea and Samaria — the biblical names Israelis use for the Israeli-occupied West Bank.

“I hereby announce the seizure of land for military purposes,” said the order, accompanied by maps showing how the housing project would soon be cut off, along with a few other Palestinian homes and some farmland.

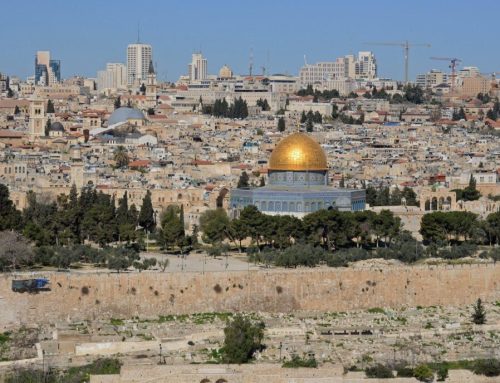

Across the valley from Beit Sahour lies the sprawling Jewish settlement of Har Homa, south of Jerusalem.

Construction began at Har Homa and Beit Sahour around the same time in the late 1990s. While Har Homa now houses thousands of Jewish families, the Beit Sahour site is still unfinished.

In 2002 the Israeli authorities issued orders for the demolition of the housing project. The orders have been frozen but still hang over the heads of the residents.

When they were first issued, construction came to a standstill for eight months as fear spread among the community. The project’s committee called together everyone with a stake in the housing and in defiance they all agreed to continue building despite the risks.

CHURCH LAND

Intended to create affordable housing for young families on land leased from the Greek Orthodox church, the project consists of 15 buildings, each with eight privately owned apartments. A community church is still on the drawing board.

Sixty-four families now reside in 10 completed buildings. Witha few exceptions they are Greek Orthodox from Beit Sahour. To buy a flat, they must earn a limited income, be in need of housing and not own land elsewhere.

Sahouri lived in his parent’s house before moving to the housing project seven years ago.

“This is the only place. There are no lands to expand,” said Sahouri. “Beit Sahour is part of our identity. We can’t go anywhere else.”

Tourism in the area has plunged severely since 2002 when an Israeli incursion into Bethlehem led to a lengthy standoff with Palestinian militants trapped in the Church of the Nativity.

This led residents of Bethlehem and the neighbouring Christian villages of Beit Jala and Beit Sahour to emigrate in large numbers, said Claudette Habash, a member of the Palestinian presidential committee for Christian affairs.

Israel’s confiscation of land to build a settlement has hit the Beit Sahour community hard.

“The expropriation of properties has been flagrant,” Habash said. “People lost hope that there is a possibility for peace.”

Housing projects like this one encourage the Palestinian Christian community to stay in their homeland, Habash said.

“In our culture, if you have a roof over your head then you are safe,” she said. “The people of Beit Sahour, if they have $1,000 in their pocket, they will start building.”

The Israeli measures faced by the Greek Orthodox housing project are a constant reminder of the instability Palestinians live in and an incentive for the Christian community to flee.

“We are seven brothers, but only three of us are left here,” said Sahouri. “The rest have emigrated.”

The Israeli military declined official comment. But a military source said security was the motive for its actions.

“The route of the security fence is determined on the basis of security considerations in order to prevent terrorist infiltrations into Israel,” he told Reuters.

Israel says its security fence has radically reduced the ability of Palestinian militants to launch suicide attacks. But Palestinians say it is a land grab.

“It’s not their property and they take it against your will,” said Yassar Qumsieh, a 30-year-old Website administrator, who moved with his wife to their Beit Sahour flat in 2006.

“I don’t know how to describe this feeling. To call it injustice seems stupid because it’s not a big enough word.”

Palestinians see the Jewish construction in Har Homa, which they call by its Arabic name Jabal Abu Ghneim, as the last rampart in a wall of settlements encircling Arab East Jerusalem, cutting it off from the rest of the occupied West Bank.

Washington has been critical of Israel’s construction plans in Har Homa. Israel rejected criticism on the grounds that it annexed the land and placed it inside the Jerusalem city boundaries that it drew after occupying the West Bank in the Middle East war of 1967.

Israeli settlement is expected to be a controversial issue in talks next week when U.S. Middle East peace envoy George Mitchell visits the region.

The security road not only prevents Palestinians from reaching the Jewish settlement, but also severely curtails the ability of the Palestinian housing project to expand.

Nevertheless, said Sahouri, “we are encouraging people to come here … We must live here, it’s our existence.”

“Here you are born in Beit Sahour, live in Beit Sahour, die in Beit Sahour,” he said. “We don’t have the mentality to sell the house, or sell the land.”

Qumsieh is also philosophical about the future.

“I’m not concerned, for the simple reason that we’re not the only ones,” he said. “When you think how many have problems like these, you feel like you’re just one of the many Palestinians in similar circumstances.” (Editing by Douglas Hamilton)