West Long Branch, New Jersey – A Muslim American woman, standing next to her new American Zionist friend, lit a candle on 20 April – the day before Holocaust Remembrance Day – in honour of those who perished during the Holocaust.

Dr. Saliba Sarsar

The flame was placed at the centre of an image of the Earth printed on cloth, as Jews, Muslims, Druze and others from Israel, Canada and the United States intently watched the flame flickering in the dark.

The 33 people were participants in a three-day conference, “Sustained Dialogue Groups in Dialogue”, held at Monmouth University in New Jersey from 19 to 21 April. The meeting enabled representatives of local Muslim-Jewish dialogue groups across the country to meet one another and share lessons learned and best practices, as well as discuss common principles and ways to network. Sustained dialogue is significant because it focuses on transforming relationships over the long term.

Tears welled in the participants’ eyes as the Muslim American woman read aloud:

“I vow never to forget the lives of the Jewish men, women and children who are symbolised by this flame. They were tortured and brutalised by human beings who acted like beasts; their lives were taken in cruelty…. May we recall not only the terror of their deaths, but also the splendour of their lives.”

This simple but profound act not only commemorated the past but also shattered stereotypes and refocused thought and action on understanding and forgiveness, passion and compassion, trust and coexistence.

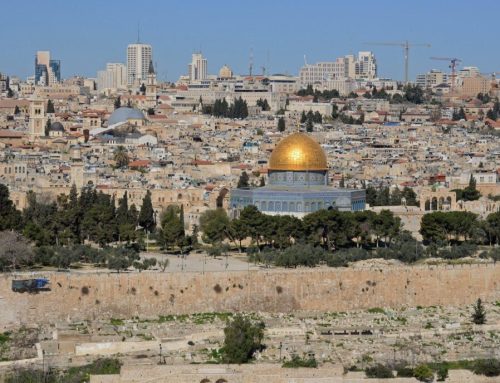

Two conferees – one Arab American, one Jewish American – were members of Zeitouna (Arabic for “olive tree”), a sustained dialogue group comprised of Arab and Jewish women in Ann Arbor, Michigan. They explained how they refused to be enemies, and how, through personal transformation, education of others and expansion of political discourse, they support a sustainable future for Palestine and Israel.

Prior to joining Zeitouna, these two participants lived on opposite sides of the ideological and socio-political divides – one being a child survivor of the Holocaust and the other a Palestinian refugee. Their commitment to social justice and peace activism helped them overcome ignorance about, and fear of, each other.

Members of dialogue groups begin their journeys where they live and work – in their own communities. Through deep conversations, social gatherings and cultural activities, they dispel phobias about “the other”, thus reducing enmity and promoting expanded understanding of reality. Although some of them are far away from Israel and Palestine, their influence cannot be underestimated as they educate the general public, advocate for a relationship-based policy that considers interests on both sides and contribute financially and otherwise to the well-being of both Israelis and Palestinians.

The commitment to dialogue and to this public peace process is also at the heart of the Jewish-Palestinian Living Room Dialogue Group of San Mateo, California. “Sustained dialogue, with its deep listening to learn, is not a hobby but a way of life”, three of its co-founders explained at the conference. The perpetual face-to-face meeting, learning and initiating occurs between members of civil society outside of government, creating a grass-roots foundation for understanding.

Sixteen years and 205 meetings of engagement have taught them that dialogue is not about winning and losing, and that “an enemy is one whose story we have not heard”. By including all perspectives – not just some at the expense of others – they create trust, and then unprecedented learning, compassion and creativity to model a sustainable culture of peace.

As representatives of each of the 11 sustained dialogue groups presented their work at the Monmouth University conference, it became apparent that dialoguing is not easy. It can uncover liberation and empowerment, but conflicting narratives and emotional pain as well. Yet as an equaliser of power, the dialogue process finally restores symmetry to relationships and enables participants to highlight similarities.

The intent of dialogue is not to reach agreement. Through storytelling and retelling, and the sharing of feelings, dialoguers connect at the heart and then grow with “no walls, no checkpoints”. New realities emerge. This process “might be hurtful but not injurious”, a Palestinian American conferee stated in a dialogue session. A Jewish American conferee added, “You do not have to be wrong in order for me to be right!”

Our personal and collective responsibility is not to alter or compromise our identity in order to change our perspectives, but rather, as a Buddhist conferee believes, “to transcend our identity so that we can arrive at a common place with the other”.

Transcendence allows us to work through the paradox of despair on the ground and find hope in dialogue. Ultimately, we become advocates for many peoples – Arabs and Jews; Palestinians and Israelis; Jewish, Christian and Muslim – equally.

Peacebuilding at the grassroots level is a strong complement to peacemaking at the political leadership level. After all, when a peace agreement is signed, it is the people who must live the peace…together.