The Israelis invited him, the Muslims are in favor of his visit. But not his own faithful in the area: most of the opposition to his trip has come from them. The reasons for the rejection. And the unknowns

Sandro Magister – Chiesa

The Sunday before leaving for the Holy Land, in a Saint Peter’s Square overflowing with faithful, Benedict XVI said in a few words what the aim of his trip will be:

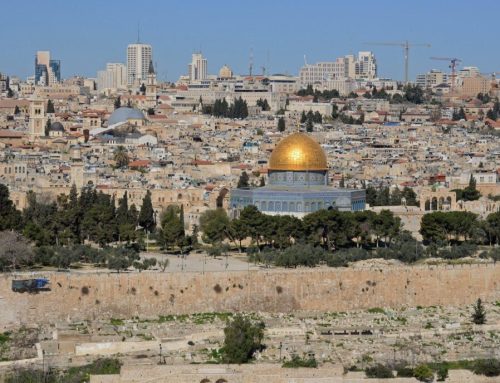

“With my visit, I intend to strengthen and encourage the Christians of the Holy Land, who must face numerous difficulties on a daily basis. As successor of the apostle Peter, I will communicate to them the closeness and support of the entire body of the Church. Moreover, I will be a pilgrim of peace, in the name of the one God who is Father of all. I will bear witness to the Catholic Church’s efforts on behalf of those who strive to practice dialogue and reconciliation, in order to reach a stable and lasting peace in justice and mutual respect. Finally, this trip cannot help but have significant ecumenical and interreligious importance. From this point of view, Jerusalem is the city-symbol par excellence: it is there that Christ died in order to gather together all of the scattered children of God.”

From these words – reiterated at the general audience on Wednesday, May 6 – it can be gathered that in order to promote peace and dialogue among the peoples and religions in the Holy Land, the pope is relying first of all on the Christians living there.

A bold wager. It’s not only that Christians has been reduced to a tiny minority in the region, less than 2 percent of the population, which is mainly Jewish and Arab. It must also be kept in mind that the Christians in the area have been the most skeptical in reacting to the announcement of the pope’s trip. Many of them, including priests and bishops, have said that his visit is inopportune.

It has taken a great deal of effort to smooth over this front of rejection. The Latin patriarch of Jerusalem, Fouad Twal, has confirmed this in an interview: the reasons of the opponents were even explained to Benedict XVI in person.

The main concern of the opponents was that the pope’s trip – in part because of his extremely positive stance on religious dialogue with Judaism – could be to Israel’s political advantage.

Benedict XVI firmly stood his ground. For its part, Vatican diplomacy did all it could to pacify the opposition.

This explains, for example, the benevolence that the Vatican showed toward Israel’s archenemy, Iran, during and after the controversial Geneva conference on racism: a benevolence that many observers judged as disproportionate.

It may also explain the silence of the Vatican authorities and the pope himself on the treacherous hanging of the young Iranian woman Delara Dalabi in Tehran. In cases of this kind, publicized all over the world, the Holy See almost always raises its voice in defense of the victims of human rights violations: but this time, it decided to remain silent.

***

It must be noted that Iran, in turn, is treating the Holy See with unusual benevolence. Receiving the new apostolic nuncio to Tehran, Archbishop Jean-Paul Gobel, in April of last year, President Ahmadinejad called the Vatican a positive force for justice and peace in the world.

Shortly afterward, he sent a high-level delegation to Rome, headed by Mahdi Mostafavi, a direct descendent of the prophet Mohammed, the president of the Islamic Culture and Relations Organization in Tehran, and a former foreign minister: one of Ahmadinejad’s trusted men and “spiritual advisers,” with whom he meets “at least twice a week.”

The Iranian delegation and an authoritative Vatican delegation held a closed door meeting from April 28-30, on the theme “Faith and reason in Christianity and Islam,” which concluded with a meeting with Benedict XVI.

There is a tiny Catholic community in Iran, which is subjected to smothering supervision. This also helps to explain the “realism” demonstrated by Vatican diplomacy in this and other Muslim countries. Discretion is believed to be more effective than open denunciation in order to save what can be saved.

For example, the Vatican has stigmatized Ahmadinejad’s repeated anathemas against the existence of Israel only once, and in veiled form. It did this in a statement from the press office all the way back on October 25, 2005. Since then, silence.

But diplomatic “realism” does not explain everything. Ahmadinejad’s anti-Jewish anathemas sound familiar to a significant portion of the Arab Christians living in the Holy Land. For them as well, the very existence of Israel is the cause of all evils.

It must be kept in mind that such thoughts do not circulate only among Arab Christians, but also among leading representatives of the Catholic Church who live outside of the Holy Land, and in Rome.

One of these, for example, is Jesuit Fr. Samir Khalil Samir, an Egyptian by birth, one of the Islamologists most respected at the Vatican, who two years ago, in a “decalogue” for peace in the Middle East, wrote:

“The root of the Israeli-Palestinian problem is not religious or ethnic; it is purely political. The problem dates back to the creation of the state of Israel and the partitioning of Palestine in 1948 – following the persecution systematically organized against the Jews – decided by the great powers without taking into consideration the populations present in the Holy Land. This is the real cause of all of the wars that followed. In order to remedy a grave injustice committed in Europe against one third of the world’s Jewish population, Europe itself, supported by other powerful nations, decided to commit and committed a new injustice against the Palestinian population, which was innocent in the slaughter of the Jews.”

Having said this, Fr. Samir maintains in any case that the existence of Israel is today a matter of fact that cannot be rejected, independently of its original sin. This is also the official position of the Holy See, which has long been in favor of two states, Israeli and Palestinian.

Not only that. For Fr. Samir, the Arab Christians living in the Holy Land, although they are few in number, are “the only ones capable of promoting peace in the region, because they do not want to address the issue in religious terms, but according to justice and law.”

According to Fr. Samir, in fact, the Arab-Israeli conflict will not end as long as there is a religious war between Judaism and Islam. Only if it is brought back to its political and “secular” characteristics can it find peace. And the Christians are the ones best equipped for the task.

***

On the eve of Benedict XVI’s trip to the Holy Land, Fr. Samir expanded on these ideas about the role of Christians in the region in an interview with the Italian weekly “Tempi.”

He said, among other things:

“Previously, the Nahdah, the Arab renaissance that took place between the nineteenth century and the first part of the twentieth century was essentially produced by the Christians. Now once again, a century later, the same thing is happening, although the Christians are in the minority in Arab countries. Today the ‘new’ elements in Arab thinking are coming from Lebanon, where the interaction between Christians and Muslims is the most lively. Here there are five Catholic universities, in addition to the Islamic and state institutions. There are radio and television stations, newspapers and magazines of Christian origin, for which everyone writes, Muslims, secularists, Christians. Today, the cultural impact of the Christians in the Middle East takes place through the means of communication: Lebanon has become the leading center for book publication in the entire Arab world, printing Saudi books, Moroccan… The Muslims also understand that the Christians are the most active groups and the most dynamic cultural elements, as is often the case with minorities. Christians in Lebanon and other Middle Eastern countries also have connections and contacts with the West, and for this reason their cultural role is fundamental. Many Muslims, including authoritative leaders, in both Lebanon and Jordan, but also in Saudi Arabia, have stated this publicly: we do not want the Christians to leave our countries, because they are an essential part of our societies.”

To this optimistic picture, Fr. Samir naturally adds the caution that Christians are in danger almost everywhere in Muslim countries. Beginning with Saudi Arabia, another country that the Holy See approaches from an impartially “realistic” stance, which culminated on November 6, 2007, with the welcoming of the Saudi king with full honors at the Vatican, avoiding any mention of the systematic violations of human rights in the country.

Returning to the Israeli-Palestian question, the role of Christians is seen more pessimistically by another leading expert on the region, the Custodian of the Holy Land, Franciscan Fr. Pierbattista Pizzaballa. In his view, today in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict “Christians no longer count for anything, politically.”

Moreover, they are the most chilly in welcoming the pope’s visit, despite the fact that he put them first on the list of the reasons for his trip.

Benedict XVI has a tough job ahead of him in the Holy Land. More than the Israelis, who invited him, more than the monarchy of Jordan, which has thrown open the doors for him, he will first have to win over the Christians in the region.