Raf Sanchez and Josie Ensor, The Telegraph

ON THE last Sunday of October, the church bells in the Iraqi Christian town of Qaraqosh rang out for the first time in two years.

The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) had been driven out, leaving behind only the dead bodies of their fighters and the churches that lay desecrated but not totally destroyed.

Christians have lived and worshipped in the region since the first century AD, and in the heady days after Qaraqosh and neighbouring villages were liberated, people spoke excitedly about a new dawn.

But in a nearby refugee camp, Thamer Ghayath, a 35-year-old father of two, had quiet doubts. Ghayath had been a security guard at his church in Qaraqosh but fled as ISIL swept in.

He said he was frightened not only of the jihadists but also of his neighbours from Sunni Muslim villages, some of whom had helped ISIL identify Christian homes, then moved into them, forcing out their occupants.

“I believe they wish to cleanse the area of all Christians,” he said. “Christians are no longer safe in the Middle East. While Daesh may be expelled for now, there will be another ISIL tomorrow.”

His fears are echoed in Christian communities across the Middle East. While 2016 may have been the year that the Islamic State was pushed back and towards defeat, its two years of violence have left Christians with wounds created by fear and distrust that may never heal.

In interviews throughout the Middle East, Christians of many backgrounds wondered aloud whether ISIL’s savagery was the symptom, not the cause, of a wider hatred against them. They said their minority faith made them targets for specific brutality.

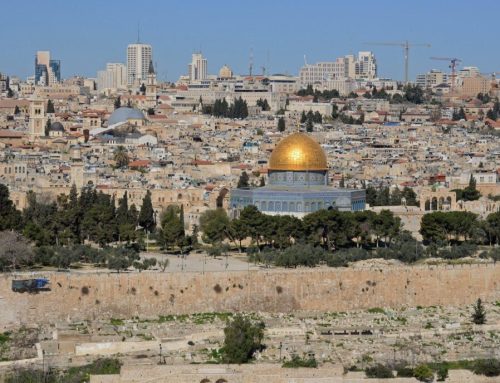

And they questioned whether there was any future for Christians in the lands where Jesus and his earliest followers once walked.

The trends are starkest in Iraq and Syria, where few citizens of any religion have been spared the horrors of war.

Before the U.S.-led invasion in 2003, there were around a million Christians in Iraq. Today there are only 200,000.

“The decline has continued to such an extent that there could be no Christians left in five years,” said John Pontifex, spokesman for Aid to the Church in Need, a Catholic charity that tries to help persecuted Christians.

The community in the Nineveh plains around Mosul is described as “the beating heart” of Iraqi Christianity and has faced the most devastation from ISIL. Much hangs on what they decide for their future.

Archbishop Bashar Warda, of Irbil, says his flock is now divided into thirds: one third is eager to return home; one third wants to quit Iraq; and the final third has not made up its mind.

Around two-thirds of Syria’s 1.5-million Christians pre-war have fled, and only the poorest remain, according to Antoine Audo, a Catholic bishop from Aleppo. Those who left were fleeing the fighting and deprivation, but Christians are also targeted for persecution by ISIL and other Islamist groups.

Syrian Christians are usually wealthier and better educated than their fellow countrymen, making it easier to start new lives abroad, and many doubt they will return. “We love our country but we no longer feel our country loves us,” said one.

The exodus of Christians is not limited to those countries worst affected by jihadist violence.

George Matar is a sprightly 69-year-old from Beit Jala, a Christian village next to Bethlehem in the occupied West Bank. The retired electrician, who speaks English with an American accent after years in the US, said many of his friends are Muslim, and Palestinians of all faiths share the same burdens and humiliations from the Israeli occupation. Now Beit Jala’s Christians have begun to wonder whether the violence seen elsewhere could happen to them too, Matar said.

“When they see news they get so scared that their neighbours might one day turn on them. They wonder what is in the minds of the Muslims.”

Five of Matar’s seven children now live in the U.S., leaving in search of opportunities and freedoms far from the Israeli checkpoints and a restrictive Palestinian culture. That trend is even more accelerated in Gaza, where there are just 1,300 Christians left among a population of 1.5?million.

There is little future for anyone in Gaza, said Natalie Sayegh, an 18-year-old student, but young Christians are leaving at an especially rapid rate. “They leave to go to Jordan and they don’t come back. They go on to America or somewhere else,” she said. “It’s too difficult here.”

The problem, say Gaza’s Christians, is not the Hamas government, but the Israeli blockade that is suffocating life.

Cardinal Vincent Nichols, the Archbishop of Westminster, when he visited a Gaza church, spoke of his admiration for “these young people who try to live today positively without knowing what their hope will be for the future”.

“All across the region there are hundreds of thousands of Christians who have faced a choice to give up their faith or give up their homes. And almost invariably they give up their homes,” he told The Daily Telegraph.

The Middle East’s largest Christian minority is in Egypt, where nine million Copts make up a tenth of the population.

Coptic Church officials were relieved when the elected Muslim Brotherhood president Mohammed Morsi was overthrown in a military coup in 2013 and replaced by Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, a traditional strongman who – like Bashar al-Assad in Syria – has presented himself as a defender of religious minorities against Islamists.

But Sisi’s authoritarian government has been either unable or unwilling to shield the Copts from terrorism and sectarian violence. A suicide bomber walked into a Cairo church during Sunday prayers on December 11 and blew himself up, killing 27 people, mostly women and children. ISIL, which has an active branch in Egypt’s Sinai desert, claimed responsibility for the outrage and Sisi declared at a state funeral that the attack cause “pain to all Egyptians”.

The bombing was just one of 47 anti-Christian incidents recorded in 2016 by Eshhad, a group that monitors religious persecution in Egypt, and many of the victims said the government did little to help them.

Take the case of Ashraf Abdu Atiyah, a 33-year old man from the Karma village in Minya province, where 500 Coptic Christians live among 11,000 Muslims. Atiyah’s neighbours accused him of having an affair with a Muslim woman and he fled the village in fear. The family twice appealed to police but were ignored, they said.

On a Friday afternoon in May a crowd gathered outside the house and, failing to find Atiyah, they set upon his 65-year-old mother, beating her and parading her naked through the village streets. The frenzied attack came to an end only when a Muslim man spread his jellabiya, a traditional garment, over her and took her to safety.

“She is devastated, she doesn’t leave the house, she sits alone with her head in hands and crying. She can’t imagine what happened to her,” Atiyah said.

There are quieter spots for Christians in the Middle East.

Jordan’s Christians live in relative prosperity although they have watched a recent spike in extremist violence with alarm, including the assassination of a prominent Christian intellectual. Lebanon’s confessional system of politics has proved surprisingly durable and Christians hold many major public positions, including the presidency. And inside Israel Christians live with security and citizenship, even if they sometimes face the same discrimination within the Jewish state as Muslim Arabs.

Two millennia of Christian history in the Middle East has seen much violence and many trials for the people known respectfully in Arabic as Masihi (of the Messiah) or disparagingly as Nasrani (those from Nazareth). But the first 16 years of the new millennium have been among the most destabilising and existential yet. They will be praying for a more peaceful 2017.

Source: Ankawa