![]() Published 8:20 AM ET Fri, 3 March 2017 | Updated 1:10 PM ET Fri, 22 Dec 2017

Published 8:20 AM ET Fri, 3 March 2017 | Updated 1:10 PM ET Fri, 22 Dec 2017

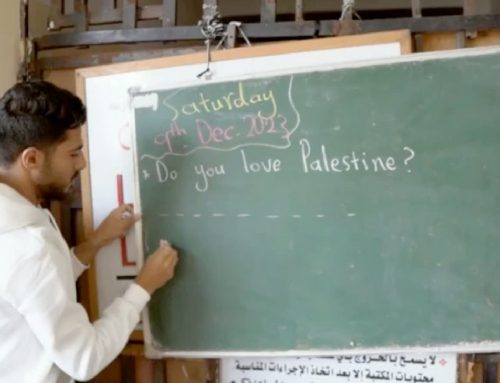

Samer Khoury is not a diplomat, which makes his self-assigned mission of restoring the little town of Bethlehem that much harder.

Despite incredible odds against increasing violent protests in the wake of U.S. President Donald Trump’s decision to recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, this businessman has been able to attract the support from heavyweight patrons of all faiths, including Theodore McCarrick, the archbishop emeritus of Washington, D.C.; Prince Talal Bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, a senior member of the royal family of Saudi Arabia; and, more controversially, Sheikh Muhammad A. Hussein, the grand mufti of Jerusalem, the Sunni Muslim in charge of the Al-Aqsa Mosque.

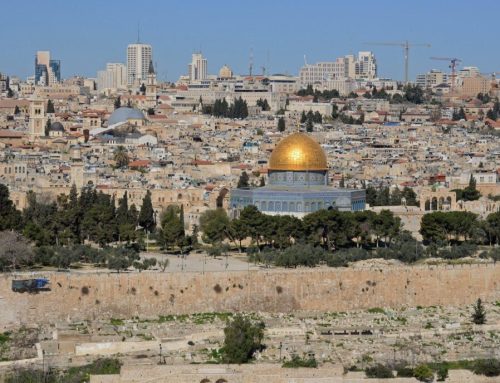

The task requires a tenacious spirit. On one hand, the unassuming Athens-based construction magnate, one of the family that owns the $5.3 billion Consolidated Contractors Co., is dealing with the Israeli occupational government, which has a say in much of what happens in Bethlehem. The Palestinian city lies just beyond the wall that separates Israel and Palestine, in between Jerusalem and the Jordan River.

The long conflict and military occupation have exacted a heavy toll on Bethlehem, which could otherwise be one of the most visited tourism destinations in the world. The GDP per capita in the West Bank and Gaza is $4,300. Bethlehem remains a poor city, where some families live in one-room homes and many young people lack jobs.

Khoury’s work and life for the people of Bethlehem are harder now in the wake of the announcement in early December by U.S. President Donald Trump that the United States recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. The announcement, which failed to mention East Jerusalem as the capital of Palestine — a long-hoped for outcome by moderates in the Arab world — sparked violent protests across the Middle East. In Bethlehem, tourism has slowed to a trickle, and there have been some protests there, too.

“What we sell is the Christian spirit and the message of hope and peace,” Khoury said.

He worries about what the next weeks and months will bring. “History has told us when something starts no one knows the end game in this part of the world,” he says.

A political morass

Fractured politics mirror the fractured religions: The main attraction in Bethlehem is the Church of the Nativity, said to the be birthplace of Christ. It has been governed for centuries by three denominations whose defense of their “zones” in the church is legendary and has sometimes come to blows: the Franciscan order of Roman Catholics, the Greek Orthodox Church and Armenian Apostolic Church.

“They are not business people,” said Khoury, sounding pained, recounting the difficulties of getting the lights strung to decorate the Church at Christmas.

But, moved by his family’s Greek Orthodox and Palestinian roots, Khoury has a new vision for Bethlehem: Within 10 years, he wants to see 3 million tourists a year thronging the narrow streets. Three years in, he said, “We’re 5 percent to 10 percent there.”

Paying it forward

Khoury’s late father, Said, founded the Bethlehem Development Foundation, a nonprofit that has so far spent about $40 million, with projects under way to further restore the Church, build playgrounds for children and buy buses to ferry tourists to sites in and around the town. The foundation also incorporated a fundraising nonprofit in the United States and plans a Washington, D.C. dinner focused in early February.

It aims to raise and spend another $60 million by 2027. “It’s a sad city when you enter,” said Khoury. “This is the center of Christianity, important for 2 billion people. My father said: ‘It is going to be a ghetto if nobody does anything.'”

David Silverman | Getty Images

A pilgrim lays her hand on the silver star in the Grotto under the Church of the Nativity, which according to tradition marks the sport Jesus was born.

Khoury, who picked up the reigns after his father died in 2014, wants to do everything from spur tourism with a new hotel and new agreements with Israeli bus companies, to helping develop jobs-training programs for students at a local university.

The streets of Bethlehem are lined with tiny shops, many selling olive wood trinkets and beautifully carved nativity sets, but they are struggling. Bassem Giacaman, one of the shopkeepers, said before the Second Intifada, his shop had revenue of $400,000 a year, and employed 12. Now, it brings in about $100,000 a year, enough to employ three people and earn him a tiny profit, perhaps $10,000. In the two weeks since Trump’s announcement, only three people have visited his shop, and he doesn’t know how he will pay his workers, he said.

Still, he stays, he said, because he wants to keep his family’s workshop alive and because he loves the Church of the Nativity. In 1948, the Christian population of the Holy Land was 18 percent; it’s now 2 percent, according to the Holy Land Christian Ecumenical Foundation.

Giacaman has tried to make his shop welcoming for everyone: it carries menorahs, nativity sets, Arabic calligraphy— and welcomes tourists who need to use the toilet. “We just try to open the door and keep things going,” he said.

Khoury said he was in part inspired to continue his father’s work when he talked to people like Giacaman. The Foundation, with the initial donation of $30 million from the Khourys in 2011, is helping the Palestinian government manage the much-lauded restoration of the Church, refurbished Manger Square, where tourist buses park, helped start a small museum, and financed a strategic solid waste management plan for the area. Among it’s long-term plans: a small shopping center and car park, a solar power station that could power small factories, and a small hotel of about 100 rooms.

Some of the projects may be funded via investments – he said he believes some projects could yield 10 percent annually—and some via donations.

Though between 1 and 2 million people visit the Church every year – exact numbers are hard to come by – few stay overnight and little economic benefit comes to the town of about 25,000 people.

A philanthropic cause

Khoury’s late father was a Greek Orthodox Palestinian who immigrated to Lebanon, founded CCC, and then moved it to Greece. “He was a true believer,” Samer Khoury said of his father.

CCC, now run by his three sons, has about 100,000 employees worldwide and had revenue of $5.3 billion in 2016, Khoury said. It builds projects of enormous scale: CCC builds or is a partner on projects such as the giant 60 kilometer Riyadh Metro in Saudi Arabia, a giant expo center in Kazakhstan, and — in the near future — oil platforms off the East Coast of Africa, Khoury said. CCC is a part owner of the power plant in Gaza, the southern part of the Palestinian Territory.

In Bethlehem, the scale of projects is much smaller. Sometimes, in the complicated politics of the town, the goals can get tripped up by something as small as a string of lights.

For instance, stringing lights on the Church of the Nativity opened a fraught negotiation between the three denominations. An extra light hanging on the wrong side of a wall might have been taken as a sign one of the denominations had ceded territory in the church to another. In the Church of the Nativity, the walls, the windows and even a crack in the floor are claimed by one of the three. “It is funny,” said Khoury, without laughing even a little bit. “It is not practical.”

He is a little frustrated, but he is not giving up.

Issam Rimawi | Anadolu Agency | Getty Images

The Church of the Nativity is seen during its restoration in Bethlehem, West Bank on November 28, 2016.

Though there are many nonprofits and aid agencies working in Bethlehem, Khoury’s effort is different, observers said, because of its breadth, Khoury’s business acumen, the money behind it and the expertise CCC is putting to the task.

“What Samer Khoury has developed is an entire mechanism to restore and rebuild Bethlehem; a city whose international reputation precedes it, but whose infrastructure, and most importantly, its people have been neglected for far too long. (He) is working … to bring hope back to the city’s inhabitants,” said Sir Rateb Rabie, CEO of the Holy Land Christian Ecumenical Foundation and a Knight of the Holy Sepulchre, named by the pope for services in the Holy Land.

The Bethlehem Development Foundation has an engineer working in Bethlehem on restoration of the Church, which started three years ago and will probably last for another three or four years, Khoury says.

Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas first convinced the three denominations to allow the restoration, but Khoury’s foundation stepped in to manage payments for the highly specialized contractors doing the work, which has included replacing the 500-year old wooden roof. Now, the restoration is moving on to restoring beautiful golden icons on the walls and an ancient mosaic under the floor that tourists tramp over on their way into the grotto said to mark the birthplace of Christ.

Among the discoveries during the restoration: a hole left from a stray bomb that fell during the 1967 War.

Against all odds

The difficulties of existing in Bethlehem, which lies just beyond the wall that separates Israel from Palestine, have defeated big companies. The InterContinental Hotels Group, for instance, withdrew its contract with the famous Jacir Palace Hotel in Bethlehem after a series of stabbings in Israel and reprisals in the West Bank. Tourists generally travel through Israel, and come via buses from Israeli touring companies, which drive in and out of the town, headed to more developed destinations on the Israeli side, as rapidly as they can. The GDP per capita in Israel is $34,800 a year.

Khoury is unfazed. “This is Israel and Palestine,” he said. “You have to expect that.”

He believes that if Bethlehem had more to offer tourists, their numbers would grow, and they would stay and spend more money. Both Israel and Palestine are seen as tourism markets with enormous untapped potential. For instance, in 2010, a comparison between Israel and Jordan found the former got about 2.8 million in tourists, compared with Jordan’s 4.5 million. About 648,000 Americans visited Israel in 2016, up 5 percent compared to the last record year.

Khoury remains hopeful. To cope with the complicated politics of the region, and the complicated religious politics, Khoury assembled an board of heavyweight patrons of many faiths.

Khoury said he invited two Jewish board members and hopes to have one join this year.

To raise more money for Bethlehem Khoury is turning to wealthy individuals, especially those with roots in Palestine. “It is like with any startup, you need a track record,” he said. “We have that now.”

On his list of targets: Carlos Slim, the Mexican billionaire whose father was from Lebanon. Khoury said he believes he’ll find many people willing to help. Donations have already begun coming, such as a $1.2 million gift from the Kuwait-based Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development, he said.

“I made a big list. These people, like our family, have connections to Palestine and have succeeded.”

He’s convinced the story of Bethlehem will attract givers. He paused, unexpectedly poetic for a businessman. “My song that I sing, I bring many people along,” he said.

— By Elizabeth MacBride, special to CNBC.com