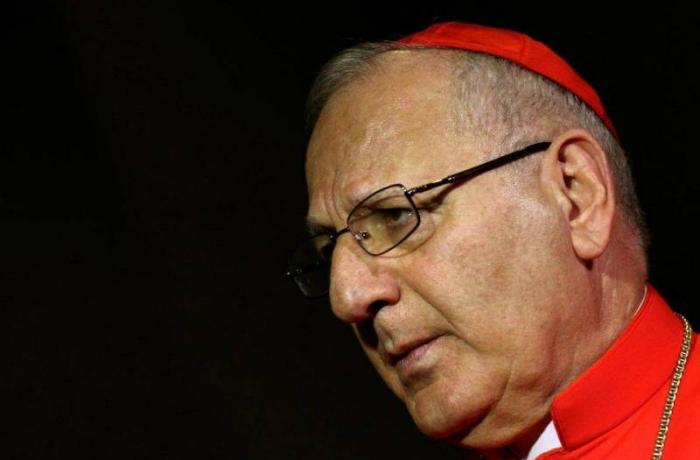

Patriarch Sako will be created cardinal on 29 June. He appeals to Iraqi Christians who fled from the Islamic State to come back and those who remain to stay. “I never imagined that such terrible things could happen to our people,” he said. Christians must help “Islam to open up, to help it develop a new reading of the sacred texts, a realistic reading that puts them in their historical and cultural context”.

Baghdad – Pope Francis will raise one of the top hierarchs of the Eastern clergy to the rank of cardinal along with 14 other bishops next Friday (29 June).

For Patriarch Sako, 70, the head of the Chaldean Church of Iraq, this title, which he will share with the Maronite Patriarch Bechara al-Rahi, will be honorific as long as the pope lives, but also associates him with the electoral college which will elect the next pope.

To know Patriarch Sako well means first recognising the modesty of a man with a low voice and affable manners who stood up against the traditions and conveniences of the clergy of his time, and sought to be ordained on 1st May, Workers’ Day, to show once and for all that he is, as a priest, the brother of workers and a working man himself.

Elected in 2013, Patriarch Sako is also the leader of the Eastern Church that has suffered the most from the infamous Islamic State group. He is a man who has felt most painfully his flock’s dispersal, a man who has screamed at seeing his native Iraq, the apple of his eyes, torn into three pieces: a Kurdish Iraq, a Shia Iraq and a Sunni Iraq.

“I never imagined that such terrible things could happen to our people,” he told French newspaper La Croix, comparing the catastrophe that struck his Church and the Iraqi people on 6 August 2014, when 100,000 people fled at night, distraught, to Kurdistan, to what the “first apostles” experienced at the time of Roman persecution.

He is bitter, without illusions about the cynicism of a West which he deems “accomplice”, obsessed by its economic interests, to the point of accepting without an eyebrow that an entire people be driven from the land of its ancestors.

Of course, today, the Islamic State has territorially disappeared, and the emblematic city of Mosul has been turned over, at a high price, to its population, but Patriarch Sako is still shaken because the break-up of his country has not yet been completely reversed and because his fellow Christians, despite his loud calls, still refuse to return to Iraq, often for the right reasons, because the virus of fanaticism continues to undermine it, even if the warlike antibodies seem to have won.

“More weight”

How does Patriarch Sako envisage his new mission as cardinal? “It will give me more weight to carry the subjects of social justice, equality and citizenship,” he told Vatican News as soon as he heard about it.

For him, everything is in this added “weight” that the title of cardinal will bring him, and which he hopes the Vatican will know how to use. He also hopes that this new function will help speed up, after years of divisions, the movement towards Iraq’s reunification and the return of the faithful of its Church. But whilst he believes in dialogue, it is not “the dialogue of salons”, but a genuine dialogue that encourages Christians in Iraq to stay in their country, or return to it; otherwise, “below a certain number, their presence will have no effect.”

Coefficient of openness

For Patriarch Sako, the Christian presence in Iraq represents an important coefficient of openness. For Christians, it is a matter of “helping Islam to open up, to help it develop a new reading of the sacred texts, a realistic reading that puts them in their historical and cultural context”. For this reason, he relies on “awakenings here and there” and pays a special tribute to scholars like Hani Fahs, who unfortunately had no followers. He also appreciates the contributions of Al-Azhar to Islam’s renewal as well as Ayatollah Ali Sistani for his ideas.

“We must remain close to all these efforts in order to defend them and to end biases and Islamophobia,” he warns.

Both fronts

Following parliamentary elections in May 2018 that changed the Iraqi political landscape, the Chaldean Church will have to fight on two fronts, national and ecclesial. At the national level, carefully keeping away from partisan politics, Patriarch Sako advocates constitutional reform in favour of a shared citizenship and strengthens religious freedom. He is also aware of the difference between faith based on lived experience and faith based on identity. The latter can lead to fanaticism and fundamentalism.

“The Iraqi experience has taught us a lot,” he says. “Of course, the Church must remain sensitive to major political issues, but she must be careful not to be politicised. Like Islam. The latter’s politicisation was its undoing. The politicisation of a religion ends up distorting this religion. I believe in a Church that serves, like that of Pope Francis, a poor, simple Church, a Church of the peripheries.”

Hostile to the image of the Eastern Christians as a “minority group”, the Patriarch Sako cites a letter he released in 2015 in which he took a firm stand against “Assyrian” militias active in Iraq and Syria. One must not “think that the solution depends on creating isolated armed factions that are fighting for our rights,” he wrote as a warning.

Stressing the need to draw “lessons from history”, he pleads, on the contrary, for a commitment to regular forces like the official Iraqi army or the Kurdish Peshmerga. “We must realise that our destiny is linked to that of all Iraqis and that is the only way to secure our future together,” he wrote in the letter, calling on Christians to “stay in the same boat as the rest of the nation to arrive safely at destination.”

“Our ambition is to build [. . .] a democratic civil society, able to manage diversity, to respect the law, to protect the rights and dignity of every citizen, regardless of their ethnicity, religion or the size of their community in the overall population,” says the text to which he refers.

Church plan

As for the Church, although aware that the call of the West is irresistible to many, the head of the Chaldean Church is fighting for the great human tide that fled Mosul, Qaraqosh and the Nineveh Plain during a night of unspeakable terror, to flow back to the abandoned territories, and not be swept away into the world of emigration. By the same token, he is trying to convince some of his clergy who fled insecurity, in very human (but not very Christian) insubordination, to come back to the country to serve the faithful.

The “concern of all the Churches” that haunted Saint Paul is ubiquitous in his life. He regrets that his clergymen “do not pray enough”, pleads for a liturgical reform that puts faith within the reach of the faithful of the 21st century and fears the contact of relativism and the “dissolution” that it entails for his flock once in the West. He finds that his followers are so fascinated by the material comfort and the civil rights that they find there that they forget the triumphant moral relativism and its destructive effect on what is the apple of his eyes, namely the family, even more so, the sense and values of the family. “Losing them would mean losing everything,” he warns.

Signs of the times

The Patriarch’s speech is a reading of the signs of the times. “The voice of the priest,” he says, “must have a prophetic breath so that the liturgy is charged with soul and hope.”

“I learnt a lot from Pope Francis in terms of simplicity and closeness,” notes Patriarch Sako, who does not have only friends in a Church that is still very much clerical and formalistic.

“This is the price we have to pay to stay in Iraq, and for our presence to make sense. We must also help each other to stay. I deeply believe in the Lord and that, sooner or later, religious freedom will come and become the rule. In the meantime, we must wait, stand firm and act.”

Fady Noun

Source: Asia News