Militiamen expelled teachers for declining to follow a Kurdish-nationalist curriculum.

Eyala Saadi lives in Qamishli, a town in northeastern Syria that was founded in the 1920s after thousands of Assyrians fled the 1915 genocide in neighboring Turkey. Eyala is 27 years old and works as a protection programs officer for a humanitarian organization. She has a degree in law from the University of Aleppo, located about 260 miles from her town. While Aleppo, the largest city in Syria, is infamous for having been the scene of large-scale devastation and carnage that earned it the moniker “Syria’s Stalingrad” among combatants, Eyala’s much smaller hometown of Qamishli and its Assyrian Christian residents have faced a different type of conflict. Theirs has lasted since 1915 but has remained a struggle fought outside the spotlight shone on the brutal fighting in larger cities.

Qamishli is a Christian center of Syria — the Assyrian Christians are ethnically different from Syria’s Arab Christians, but they’ve suffered from similar threats of persecution on the basis of their ethnicities and religion. Qamishli’s pre-war population was about 40,000, with 25,000 belonging to the ancient Syriac Orthodox Church. Today, half of Qamishli’s Assyrian Christians are gone.

Eyala told National Review that many Christians have left Qamishli for other parts of Syria or even Europe. “They emigrated after many explosions in their own neighborhood, because no one will protect them,” she said. But Assyrians are also facing what Eyala describes as a quieter persecution, one that isn’t always as physically violent as bombs, though it could repeat the ethnic erasure that prompted Assyrians to flee from Turkey to Qamishli a century ago.

In early August, reports came out of Derik, a heavily Assyrian-populated town in the same governorate as Qamishli: The Kurdish self-administration in Syria, a self-declared governing body in northern Syria that isn’t recognized by any international state or organization, ordered the closing of schools for failing to register for a license and for rejecting the new curriculum approved by the Education Authority. A similar notice was issued to schools in the nearby town of Derbesiye.

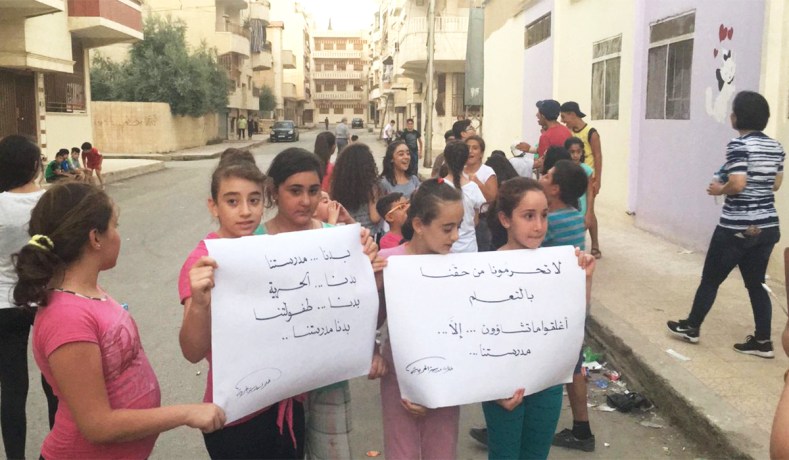

Only a few weeks later, private Assyrian schools in Qamishli were also targeted. Militiamen from the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (the PYD, the Syrian face of PKK, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, a Marxist-Leninist group based in Turkey and Iraq that is classified by the U.S. as a terror organization) and the Sutoro (the Kurdish-aligned Christian forces) entered private Assyrian schools and expelled all administrators and teachers. When the school staff refused to turn over their keys, the militiamen broke the existing locks and replaced them. Hundreds of residents staged protests, tearing down signs that read “school closed” and breaking the new locks. Teachers were expelled, and hundreds of local residents protested that same afternoon. Children held up signs reading “Don’t deprive us of our right to education” and “We want our schools, our freedom, and our childhood.” Priests led a crowd of residents carrying Syrian flags, often chanting “We will remain Assyrians and die in this land” as the Sutoro forces fired gunshots into the sky to intimidate the protestors.

These private schools have been administered by the Syriac Orthodox Church Diocese since 1935, serving Assyrian, Armenian, Arab, and Kurdish communities. They’ve offered classes in Assyrian as a liturgical language while following the Syrian government’s curriculum. Schools run by the Syriac Orthodox Church were unable to apply for the licenses because they rejected the proposed Kurdish curriculum, which has nefarious motives, according to local Christians: The Kurdish self-administration that is attempting to foist the curriculum on students is seeking to erase Christians’ existence in order to create Western Kurdistan through ahistorical accounts and Kurdish-nationalist propaganda that isn’t recognized in higher-education institutions within Syria. Students who attended schools with this curriculum effectively couldn’t attend universities within greater Syria or beyond because this curriculum isn’t recognized anywhere outside the territory that the self-administration is attempting to govern. As a result, parents would have to leave Qamishli to enroll their children in schools that universities would recognize.

“Every Assyrian and Christian knows the self-administration is using the curriculum as a weapon to implement their ideological end goals,” Eyala said. “Bishops and their members all protested — we don’t accept their curriculum. They want to achieve a Kurdistan region in Syria like they did in Iraq by driving us out.”

With the advent of the Syrian war in 2011, Christians of all ethnic backgrounds within the country were at risk of violence, especially those who were located in territory that ISIS controlled. Since then, estimates show that nearly a million Christians have left Syria, although many are returning as conditions improve. Assyrians, unfortunately, still face discrimination and fear for their future.

According to Max Joseph, a board member of the Assyrian Policy Institute, the Kurdish self-administration is actively harming the prospects of Assyrian survival in Syria through its attempted overhaul of the education system, forced conscription in the Kurdish-aligned YPG (People’s Protection Units, a militia), parallel tax systems that double the tax Assyrians pay, and extensive harassment and intimidation of Assyrians who resist their policies.

By : MARLO SAFI

Source: National Review