“Creativity takes courage,” the well-known artist Henri Matisse said. This statement is true particularly in regimes where there is little freedom of expression and many taboos concerning nationality, religion, history, politics, and other issues.

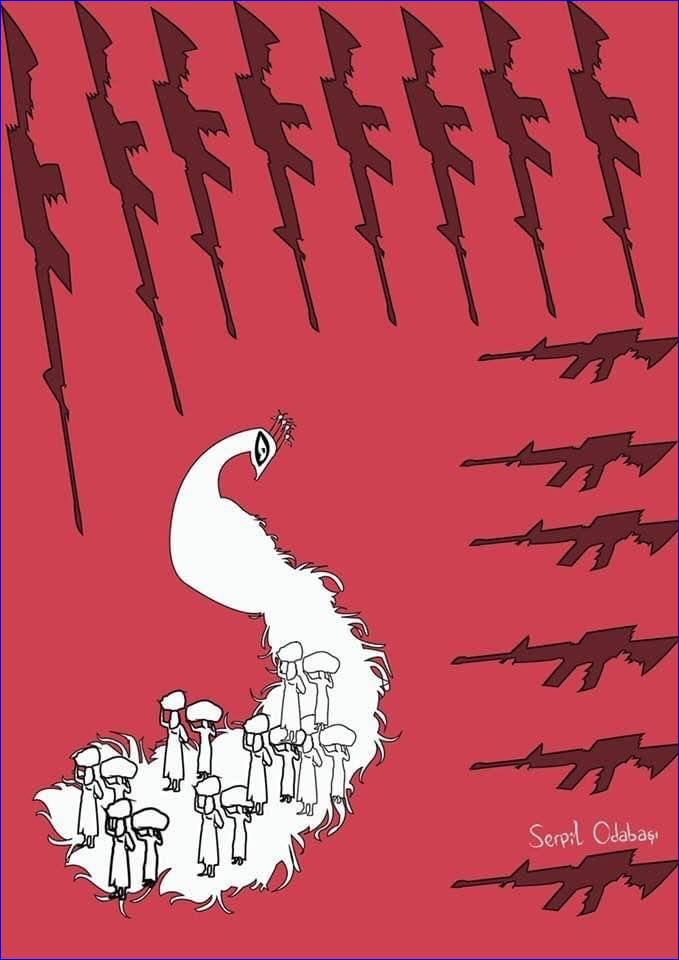

Courage is rarely found in oppressive regimes such as Turkey. But Serpil Odabaşı, a prominent Kurdish artist, has produced ground-breaking art and has shed light on many human rights abuses both in and outside Turkey.

Odabaşı is from the city of Diyarbakir. She studied art at a university in Ankara, then worked as an art teacher in Anatolia and Istanbul in the 2000s. She encountered racist pressure and attacks because of her Kurdish identity and art. She held over thirty exhibitions across Turkey, and left her country for Canada in 2011.

As an artist, Odabaşı has been put on trial for “insulting Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdogan”. An arrest warrant has subsequently been issued against her.

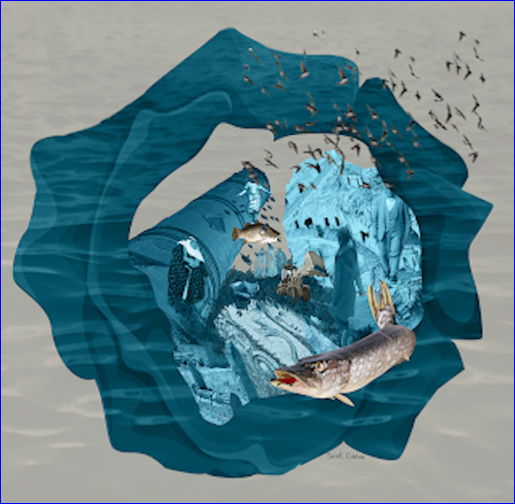

She challenged the supremacist official narratives from the Turkish government, and for that she has been targeted for years. In her many paintings and drawings, she has dealt with issues such as massacres, wars, militarism, racism, and women’s rights, among others. Her artistic works have been widely shared on social media, used as book or magazine covers, theatre posters, as well as in articles and demonstrations. She worked for Turkey’s Human Rights Foundation in the late 1990s and has written several columns about human rights abuses in the country.

“I try to take my courage from those who do not have a voice or whose voices have been silenced,” Odabaşı said. “Those who have been murdered, jailed or forcibly disappeared for their ethnicity, religion, language, sexual orientation or political views. They have been so unjustly silenced. But I could still speak or have the strength to express myself. So through my art, I have been trying to be their voice as much as I could. I think this is where my inspiration comes from”.

Odabaşı points out that while she has studied the history of Turkey’s persecuted non-Muslim peoples (such as Assyrians, Armenians and Anatolian Greeks), her interactions with these peoples in Turkey have been almost non-existent. Many members of these populations were murdered or forced to leave Turkey.

“I encountered very few traces of Assyrians and other Christians when I was living in Turkey,” Odabaşı said. “This is very painful. There are partly preserved buildings made by Greeks or Armenians in Istanbul, but in other parts of Turkey, properties belonging to these peoples have largely either been transferred to the state or seized by private citizens. And Assyrian lands and properties are still confiscated.

Serpil Odabaşı)

Serpil Odabaşı)“In the 1990s, I never saw the Armenian and Assyrian neighbors whom our elders told us about. I don’t know what happened to Maria, who put henna on my mother’s hair, or to the other neighbour who brought my family hot cross buns at Easter. When my awareness about Christian and other people in my hometown increased, there was no one left to ask about these issues. My mother lost her life when I was young.”

Turkey’s southeast region of Tur Abdin, which means “the mountain of the servants (of God)” in the Assyrian language, was once the cultural and religious center of the Assyrians. But today it is home to a small Assyrian minority.

The population of Assyrians, Armenians, Greeks and Yazidis collapsed in Turkey largely due to the 1913-23 Christian genocide toward these communities. Assyrians call the genocide “Seyfo”, which means “the sword” in their language, for during the genocide swords were often used to murder Assyrians.

Sadly, persecution against the survivors of the genocide did not stop even after the genocide. In 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne, which recognized the boundaries of the state of Turkey and granted some rights to religious minorities in the country, was signed. But it excluded Assyrians and unlawfully left them outside the treaty’s protection. Because of this exclusion, Assyrians still do not have the right to education in their mother tongue. Neither can they establish their own schools.

Serpil Odabaşı)

Serpil Odabaşı)When the conflicts between the Turkish military and Kurdish PKK escalated in the 1980s and 1990s, Assyrians, Armenians and Yazidis in the region were trapped. Many have fled their ancient homeland, and continue experiencing rights abuses. According to a 2019 human rights report:

“Assyrian families determined to defend their rights on their land became the targets of a highly antagonistic campaign, accused of being ‘obstinate’ and challenging the region’s powerful tribes. The more they resist, the more anger they face.”

Odabaşı thinks that to help stop these abuses, intellectuals from Turkey should aim at forming real, egalitarian solidarity with the persecuted peoples in Turkey who are on the verge of extinction.

“I am not talking about supremacist, condescending approaches that believe that they are doing a favor to persecuted peoples in the region by ‘including’ them in their political or intellectual endeavors,” Odabaşı said. “Our hegemon identities are always an obstacle before forming solidarity or togetherness with others; a ‘teacher’ mentality always develops. However, the first condition of living and creating equally together with those around us or with those we have deeply hurt is having an equal eye distance to whomever we wish to communicate with. And to achieve that, we need to get rid of all kinds of dangerous, supremacist illusions,” Odabaşı said.

“Serious efforts,” she added, “both by the Turkish government and Kurdish political movement in Turkey, should be made to help Assyrians and other Christians to return to the lands they have had to leave, to help them get back their stolen properties, preserve their native languages, and help them participate in politics and every sphere of life freely and safely.” She continued:

“Compensation should be paid to the returnees by the Turkish government. The Assyrian right to education in their mother tongue and multilingual municipal management in cities across Turkey are essential. Their language should also be recognized as an official language of Turkey. But it is obvious that Turkey is far from achieving this level of democratization. The fate of an elderly Assyrian couple in Turkey is a demonstration of this reality. On January 11, Hurmuz Diril (71) and his wife Şimoni (65), were kidnapped from the Assyrian village of Mehr, Kovankaya in the province of Sirnak. Simoni’s dead body was found on March 20 but her husband is still missing. So Assyrians and other Christians do not still have the right to life in Turkey today.”

Turkey’s dominant mentality of “one language, one nation, one religion, one flag” appears a significant barrier to making these essential reforms in the country. Hence, rights abuses against Christians still abound. Assyrian priest Father Sefer Aho Bileçen of the Saint Jacob Church in Mardin’s Nusaybin district, for instance, was arrested on January 10. A peaceful man who leads a monastic life is still tried for allegedly “being a member of the PKK.” His next trial will be held on November 3.

As a critical artist that has been persecuted for her art, identity and political views, Odabaşı is calling on her fellow artists, Kurds, other citizens of Turkey, and the international human rights community to show more solidarity with Assyrians, Armenians, Yazidis and all other indigenous, persecuted communities in her home country.

By: Uzay Bulut

Source: aina.org