From queens, prostitutes, warriors and saints of the past to the commitment of today’s women in the Palestinian civil society

There are few women we remember in our mythical or lived past, and those few are often mentioned just because they acted like men. This is also true in the area of ancient Palestine, an area characterized by societies that have traditionally relegated women to the domestic sphere, preventing them from emerging publicly in the community and leaving a trace of themselves.

Among the most famous, I have chosen a few examples in which this aspect is particularly relevant.

According to the Bible, Jezebel, princess daughter of Ethbaal, king of the Phoenicians, marries Ahab, son of Omri, king of the northern Israelite kingdom in Samaria. Their union represents a political alliance, which brings advantages to both the parties. As a matter of fact, Samaria was a very fertile region compared to the surrounding territory, but the exceeding agricultural production had to be marketed and there was no better way than to turn to the Phoenicians who lived along the coast.

They were famous for their trading skills. The road that connected the capital Samaria (today the small Palestinian village of Sebastia) with the Phoenician ports on the coast, was for centuries a strategic commercial axis for the kingdom.

After her wedding, Jezebel, emerges as the real authority and in the Bible she is described as powerful, wicked and prostitute, this last epithet with no reason at all. Actually, her fault was having dared to bring the cult of the Phoenician god Baal in the kingdom of Samaria, challenging the prophets of Yahweh, god of the Israelites.

As an evil wife, she negatively influences king Ahab, by manipulating him in order and forcing him to kill a man who didn’t want to sell him the vineyard. She will pay dearly for this.

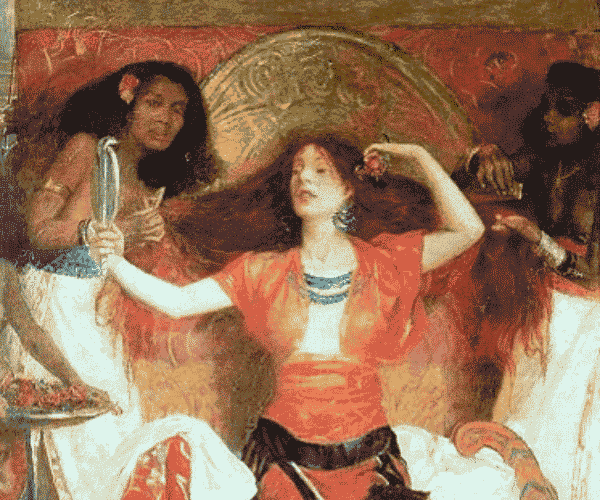

DopAfter the killing of all the men of the dynasty by the hand of Jehu, the successor supported by the prophets, Jezebel is aware that her destinity too is marked. She is the real power to destroy. Jezebel, with calm and courage, prepares herself to die. While Jehu, drenched in blood, gallops towards her, she paints her eyes with kohl, combes her hair and awaits his arrival by the window of the palace. Jehu orders his servants to throw her down.

Her body is trampled by the king’s horse and left to feed the dogs. The few remains will be compared to the manure on the fields.

Over the centuries, the story of Jezebel becomes the feminine stereotype of the woman who seduces, the power-hungry woman, who dares fighting against the prophets and god himself. A true tempting demon, but, on the contrary, to feminists, she becomes one of the most intriguing women of the Scriptures, a woman who imposes herself.

In fact, the Bible describes her to us as if she were a man. Jezebel acts and speaks in an arrogant and inappropriate way for a woman in that cultural background. In a world where women were not allowed to speak directly and determined in public. Jezebel does so in front of the king and the prophets. It is evident that she is a foreigner and inadequate to the role destined to a woman in the patriarchal Israelite society.

Mavia, the warrior queen

Turning to historical sources, another woman responds to a male logic, super-violent and superhero: the fighting queen Mavia (in Arabic Mawiyah bt. ‘Afzar). Mavia is an Arab warrior queen, who at the end of the fourth century AD. (she died in 425) found herself defending Christianity and the Roman Empire’s frontier to the desert.

Although this revolt of the Arab tribes is historically very important, the scarcity of sources and the lack of relevant archaeological or epigraphic materials makes it particularly difficult to reconstruct the details surrounding it. Scholars have focused particularly on trying to shed light on the various aspects of the role of the Arab tribal confederations on the southeastern frontier of the Roman Empire, but very little has been written about Mavia, a Christian woman, who headed a confederation of Arab tribes. And probably because she was an almost unknown woman. What we do know is that in late 377 or early 378, at the height of a serious political and military crisis during the reign of Valens (who reigned between 364 and 378), the Arab tribes of the Tanūkhids rebelled.

.

The Roman military authorities were unable to tame the revolt and were defeated by the nomadic tribes, led by their queen Mavia, who had taken over leadership of the confederation upon the death of her husband the king, al-Hawari in 375.

It is unclear why the tribes rebelled, perhaps for religious reasons, since Mavia was an orthodox Christian and Emperor Valens an Arian. Or perhaps because upon the king’s death the tribes considered the agreements the king had signed with the empire to be no longer valid and wanted to renegotiate.

The fourth-century monk Rufinus of Aquileia writes: “Mavia, the queen of the Saracens, began to shake the towns and cities on the borders of Palestine and Arabia with fierce attacks,” devastated the provinces and “destroyed the Roman army in frequent battles, killed many and scared away the others” (History of the Church 11.6).

Sozomeno (d. 450), a scholar of Gaza, lived shortly after the events. He relates that following the death of the “king of the Saracens” the peace that had existed between the Romans and the nomadic tribes dissolved and Mavia, the king’s widow, found herself at the head of the nomadic confederation. He, too, describes how Mavia then led several destructive attacks into Phoenicia, Palestine, and as far as the regions of Egypt.

The peace treaty

According to Sozomeno, the Romans had underestimated the Saracens, led in person by Mavia, and suffered a serious defeat.

The Arabs considered this battle a great victory over the Roman Empire and still (in its time) commemorated Mavia and his rebellion in their odes and songs.

The Romans were forced to negotiate with Mavia for peace, and The fifth Century Ecclesiastical History of Socrates Scholasticus points out that the revolt of Mavia and his tribes did not stop until the monk Moses was ordained a bishop. This was the prerequisite for the peace treaty.

According to Socrates, Mavia would then continue to defend the empire, going so far as to send his confederates to help defend Constantinople attacked by the Goths. It seems, therefore, that the condition that Mavia placed for the end of the revolt was one.

The ordination of the monk Moses, of Arab origin, as bishop of his tribe. According to sources of the time, Moses in turn then converted many Saracens to the Christian faith. The treaty was short-lived, however, and in 383 another Tanūkhidi revolt was crushed by the Romans.

Saint Pelagia, monk of Antioch

The third and final example from the past actually applies to three. It is a common condition of women of which traces remain in history, to be prostitutes. If the prostitute then repents, then she is destined to be remembered forever as a saint. There are several women who have lived this path, first of all Mary of Magdala, who in the Middle Ages synthesized and incorporated the stories of other Marys her contemporaries.

Also her sin is not clear; in the Gospels it is written that she was possessed by seven devils, but in the tradition she became the harlot quintessentially.

After her, other women went through the experience of sin and redemption, and one in particular is linked to the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, where her burial place still stands today.

She is Pelagia, an actress from Antioch, who lived in the fourth or fifth century and was also considered a prostitute, given her economic independence, autonomy and beauty.

Her story is told by James, a deacon of Edessa. James relates that Bishop Nonno, a desert monk, was in Antioch in front of the church with a group of bishops while the beautiful Pelagia, dressed in precious clothes and jewels, accompanied by festive young men and girls dressed in gold, passed by on the street.

The bishops avert their gaze from the sinful woman, who has her head and shoulders uncovered, but Bishop Nonno observes her attentively for a long time and turning to the others confesses his delight before the marvelous beauty that God has given to the woman.

Not only that, he reflects on the care that the woman took to make herself beautiful for her lovers, while Christians made little effort to make their souls splendid before God.

A life dedicated to prayer

James’ narrative is a device to highlight the holiness of Nonno. In fact, the bishop begins to pray for Pelagia, so that her beauty will not be subjected to demons. Thanks to his dedication, her prayers are answered: Pelagia feels the desire to enter the church during one of his sermons and she converts. She asked the Bishop for baptism. Then, she left all her possessions to the poor and the sick, and she will leave, dressed in men’s clothing, for Palestine.

Only the bishop was aware of the woman’s decision and three years later, when the deacon James also left for a trip to the Holy Land, he asked him to bring his greetings to the monk Pelagio. Having arrived on the Mount of Olives, James struggles to make contact, through a small window, with the monk locked in a cell. He is solitary, in prayer, considered a saint by all those living in the region. James does not recognize Pelagia, by now withered and thin from so much fasting, and asks for her blessing. Shortly after this encounter with James, Pelagia died. Only at the moment of preparation of the body for burial do the other monks discover that it was a woman. And that is how James tells her story.

Egeria, the first author of of the journey to the Holy Land

In reality, it was not unusual in the early Christian period to find women praying on the Mount of Olives.

It is a female pilgrim perhaps from Galicia, Egeria, the author of one of the first travel itineraries to the Holy Land. At the end of the 4th century, Egeria describes, among others, the rites that were celebrated on the Mount of Olives and the presence of female convents, but these women lived in communities, and Egeria herself probably belonged to a female congregation, because she dedicates her book to her distant sisters.

Instead, Pelagia, as a woman free from the control of relatives and poverty, became a man in order to live in peace and without risks the choice of solitude and prayer. Her body is buried in the same cell on the Mount of Olives that begins to be a destination for pilgrimages from the sixth century.

The veneration is such, that even the other monotheistic religions of Jerusalem appropriate the narrative of the sacred tomb of a woman.

Even today, on the Mount of Olives,, a small gate leads to the controversial tomb, dated by scholars to the Byzantine period. We can see it just below the place where the Christian tradition celebrates the Ascension of Jesus.

The dispute of the sacred tomb

According to the Christians, For Christians it is the cell and tomb of Pelagia. The Jewish tradition, based on rabbinic writings that placed it south of the Temple Mount, venerated this place until the nineteenth century, the tomb of the prophetess Hulda, who lived according to the Bible around the seventh century BC, and descended from another famous repentant prostitute of the Bible, Rahab, who had allowed the Jews to conquer Jericho by secretly welcoming them into her home.

According to the Muslim tradition, buried in the tomb is Rābiʿa al-ʿAdawiyya, born in Basra, an exemplary Muslim ascetic and mystic in the eighth century CE. A virgin and unmarried to devote herself totally to prayer and teaching a female community, she is considered the mother of Sufism.

The mosque built above her tomb and the main road that passes in front of it are also dedicated to her.

Two keys allow access to the place. One is held by the Muslim family that also takes care of the mosque, and the other by a Greek Orthodox Christian monk. Saint Pelagia was forced to wear the clothes of a man in order to be able to dedicate herself peacefully to the hermit’s life. Apart from the interest in her life, the place reflects the importance of Jerusalem for female religious figures in Judaism, Christianity and Islam. But this is a complex issue that goes beyond our reasoning.

The push for change starts today from the local community

Let us then return to women in the context of Palestinian civil society and face the present. From the exemplary great stories of a few exceptional protagonists, who are remembered precisely for this reason, we try to tell the small stories of the multitude of ordinary women, who every day have to face with their families the challenge of survival, in a dramatic context of denial of the most basic human rights.

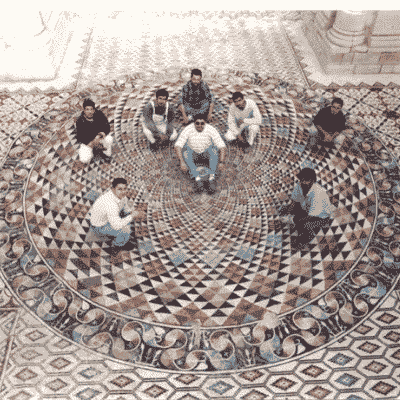

Today’s women share with their ancestors the extreme difficulty of leaving the domestic sphere, but the drive for change is becoming increasingly urgent. We are talking about the direct and concrete experiences of the projects developed in the Palestinian Territories over the last twenty years. The projects originate from two non-governmental associations, both members of the Phoenicians’ Route: the Italian Associazione pro Terra Sancta and the Palestinian Mosaic Centre. Two associations often engaged together, since the late nineties of the last century, in the preservation of cultural heritage through the involvement of local communities.

Their work begins in Jericho, in collaboration with the local government authorities, who select only boys to participate in a training activity in the field of cultural heritage conservation. It will take a few years and the decision to work in the associative and non-governmental sector to be able to include the first girls. They will be the first female technical restorers in Palestine. It will not be easy. Traditionally, newly married girls follow their husbands. And in the context of a serious shortage of work, many young Palestinians emigrate to neighbouring countries, especially the rich Gulf countries. Our first trained girls all emigrated just after marriage.

Mosaic Centre’s results

The objective of the projects carried out has never been simply to restore or enhance monuments for touristic and economic purposes. The basic idea, which will remain constant in all future actions, is to use local resources to make the resident communities grow culturally and socially. Sam from the economic perspective, especially those in economic and social difficulties. Giving the opportunity to participate, laying the foundations for communities to use their resources for their own growth. Women could not be excluded, and after years of trying, starting in the late 2000s, finally some of the girls are staying. Special arrangements will be needed.

The Mosaic Centre association is supported by pro Terra Sancta, the Franciscans of the Custody of the Holy Land and a number of international institutions

The Mosaic Centre has implemented numerous measures for its female employees. For example, the girls are able to take even extended periods of maternity leave, guaranteeing their return to work and maximum flexibility in their schedules.

Some of the trained girls return to work in the Mosaic Centre even many years later. They are always welcomed with care and attention to specific needs. Through its projects, the Mosaic Centre team has gradually grown.

From the first two male mosaicists in 2003, a group of twenty-five boys and girls was born and today they collaborate permanently in the association. The girls have gradually reached almost 50%.

In the course of time, the two associations have started interventions to safeguard historical buildings, saving the historical center of the town of Sebastia from degradation and abandonment. Here, and in the nearby village of Nisf Jubeil, the local community, mostly female, successfully manages some guest houses, a pottery workshop, a craft store and a community kitchen.

In the pottery and mosaic workshops, the girls involved in handicraft production bring their children with them, who are cared for by the entire group.

Care is taken to keep them in open or protected spaces, but in this way it is easier for the girls to get to work

For some years now, the Mosaic Centre has been hosting in Jericho an increasing number of groups of tourists and pilgrims. Unfortunately, with the heavy exception of the last two years of pandemic. The pilgrims always find in the visit to the center a moment of fellowship and knowledge. Here too, it is the women who are involved in preparing meals and collecting benefits. Some activities are dedicated exclusively to women, as in Bethany. Here, in fact, the women’s associations of the village are involved in the creation of local handicrafts to be sold to tourists.

In this case the production of soaps, creams, essential oils and scented candles has been started. These products refer to the Christian tradition that links Bethany to the anointing of Jesus by Mary, sister of Lazarus, with spikenard oil.

Attention is always paid to the little girls by involving them in awareness activities that are organized with schools or local associations. Examples of this are the art workshops or educational visits, to give them educational opportunities, growth and fun outside their home. Wet start from there, to build a fairer future.

www.proterrasancta.org//