The priest-director of the Cultural Heritage Office for the Custodia Terrae Sanctae, or Custody of the Holy Land, in Jerusalem, opened a drawer of vestments and casually dropped an unexpected historical tidbit about a clerical chasuble he was showing a group of foreign guests. The chasuble was part of a collection of vestments that the archbishop of Paris wore for the marriage of Emperor Napoleon III of France with Empress Eugenie, and which the empress later donated to the church in the Holy Land.

The gift was part of an imperial tradition, it turns out, that accounts for no small number of European religious art objects and other treasures to have been collected and preserved in the Holy Land even as many similar treasures back home were lost, looted, and destroyed over the course of European history.

Some of these objects cared for by the Franciscans in the Holy Land, including a collection of 13 church bells discovered hidden in Bethlehem and dating back to the Middle Ages, have traveled to some of the great museums of the world.

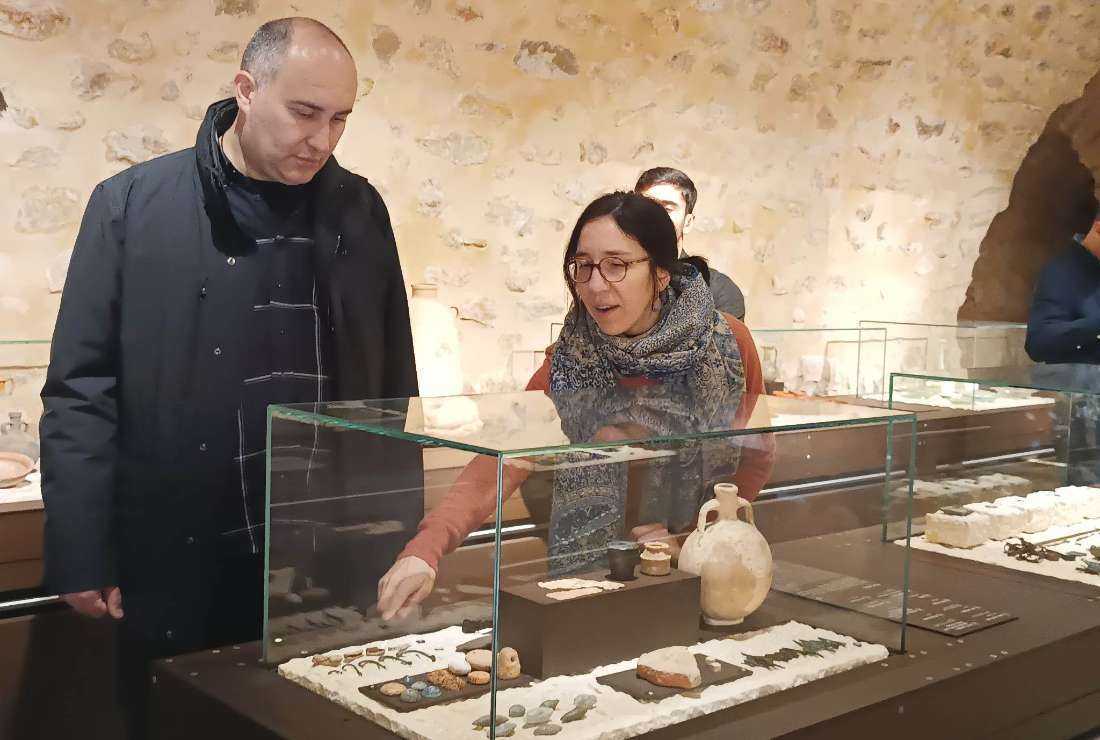

But now they will have a permanent home in Jerusalem as the Custody of the Holy Land moves forward on creating a new “Historical Section” of its popular Terra Sancta Museum, which opened to the public in 2017. The museum is situated at the Church of the Flagellation, the first station of the Way of the Cross in Jerusalem. Until now, that section has been limited to archaeological artifacts from the first millennium.

A new section of the museum will serve as a point of dialogue and exchange with the local Muslim, Jewish, and Christian communities — as well as pilgrims and visitors of all faiths and backgrounds who come to Jerusalem to explore its history and cultures.

“We want to make a Christian museum here in Jerusalem so there is something Christian to occupy the space of culture even if you are only one and a half percent of the population,” Franciscan Father Stéphane Milovitch, director of the Cultural Heritage Office for the Custodia Terrae Sanctae, told OSV News. “The church is still here and has 2,000 years of presence here; it can be a bridge with the different communities.”

The Franciscan Friars arrived in the Holy Land in the 13th century and have an uninterrupted presence here for the subsequent eight centuries during which time they occupied a unique footing as caretakers of the holy places. They provide a source of spiritual care to pilgrims from abroad and in service to the local Christian communities of the greater region, including Bethlehem and Jerusalem.

Today the Custody cares for some 50 Christian shrines and parishes and until 1850 was the only Catholic religious order serving the Holy Land. That meant the Franciscans were in a unique position to serve as a voice of the Catholic Church with the various Islamic rulers — some of which had hostile relations with the church following the Crusader era.

Over the centuries, European monarchs sent gifts and religious treasures for use in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and which have been preserved here. But the Custody also preserved its centuries of its own archives, containing singular records of communications with the local rulers as well as baptismal and marriage documents of the local Christian community.

One well-preserved collection is that of some 450 earthenware pharmaceutical pots from the 17th and 18th centuries underscoring the space the friars occupied as medical doctors and pharmacies: The first friar-doctor sent to the Holy Land by Pope Pius II in 1460 was Brother Baptist of Lubeck. The medically trained friars cared for visiting pilgrims as well as local communities.

“We had the biggest pharmacy in the Middle East,” Father Milovitch said with pride. “Even today the Christian hospital, St. Joseph, receives patients from many cultures; many ladies go to give birth at St. Joseph Hospital but also many Muslims from the West Bank come to be cured; we try to make bridges with the community.”

“We would like to display the pharmacy and how it used to be before — through some works of art we can show the church took care of the body and health of everybody, and not just since the Second Vatican Council but even before,” the priest added.

The new Historical Section of the Terra Sancta Museum will be installed at the heart of the Franciscan headquarters in St. Saviour’s Monastery. It will be divided into two parts: the history and mission of the Custody of the Holy Land, and the Treasure of the Holy Sepulcher.

Rare collections of paintings, sculptures, archival documents, and gifts from European courts — even a 13th-century gilded copper crosier of the bishop of Bethlehem — will allow pilgrims to deepen their knowledge of the sanctuaries and discover the beauty of the liturgy in the Holy Land, according to the museum’s organizers.

There also is a research element to the project with international partners anxious to assist and learn from the collection. Here too in the Holy Land, a discovery was made in 1906 of a French-made pipe organ believed to be the oldest such pipe organ in Christianity and which remains fully original.

That organ is expected to be part of the new museum collection. Researchers have made a facsimile to better understand the nature of liturgical music from the Middle Ages, according to Father Milovitch.

The Franciscan collection also includes a one-of-a-kind set of written communications with Egypt’s Mamluk Sultanate dynasty, which held sway in the Holy Land from 1260 to 1516. However, little documentation has survived from the period.

“We have many thousands of documents we kept over the years because our archives were never invaded,” Father Milovitch said.

Researchers from France as well are keen to explore the local icons produced in Jerusalem over the centuries and to understand how the Jerusalem school of iconography compares with other iconography styles.

The museum also will include an extensive collection of locally produced mother-of-pearl religious art objects along with Palestinian jewelry. Mother-of-pearl craftsmanship was introduced by the Franciscans in the 16th century to enable local Christian families in Bethlehem to support themselves. That art became part of Palestinian cultural heritage.

“The patrimony we have interests not only Christians but also humanity (in general), because everybody likes music and everybody likes art,” Father Milovitch said, adding “it is important to create a bridge with the different cultures.”

By Tom Tracy, OSV News