During recent excavations in the ancient Assyrian city of Nimrud in Iraq, a team of archaeologists from the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology uncovered an exciting bounty of artifacts and ruins. Every new discovery that emerges at the one-time capital city of the legendary Assyrian Empire is now considered a major triumph for history, as researchers and cultural authorities in Iraq continue to resurrect a revered archaeological site that was badly damaged by terrorists from the notorious Islamic State in 2015 and 2016.

Assisted by Iraqi colleagues, the Penn Museum researchers found a variety of stone monuments inside the ruins of two grand structures built by the ancient Assyrians, who ruled the region from the 14th through the seventh centuries BC. The structures excavated were a 2,800-year-old palace constructed during the reign of the Assyrian king Adad-Nirari III , and a temple dedicated to the goddess Ishtar that was almost totally destroyed when the city of Nimrud was attacked by an invading army in 612 BC.

The Assyrian Goddess Ishtar, Revealed

The recently completed excavation season is the second to take place at the recently reopened site of Nimrud, which was known as Kalhu to the Assyrians and called Calah in the Bible. During the first season the same team of Penn Museum and Iraqi archaeologists discovered the partially shattered stone remains of the palace of Adad-Nirari III , who ruled the Assyrian Empire from the capital city of Nimrud from 810 to 783 BC.

Exploration of the palace and its ruins continued this year. But the Penn Museum researchers were anxious to expand their work to encompass the obliterated grounds of Nimrud’s Temple of Ishtar, which was located adjacent to the palace. And it was here that they discovered something remarkable.

Working under the direction of Dr. Michael Danti, the director of the Iraqi Heritage Stabilization Program, the archaeologists discovered multiple fragments of a broken stone monument. On one of these pieces there was an actual carving of the goddess Ishtar, which is the first such image to be found anywhere in Nimrud.

Dr. Danti has been leading excavation and heritage rescue programs in Iraq, Iran and Syria since the 1980s. Given his vast experience in the region, his reference to this discovery as ‘spectacular’ highlights its special and unique nature.

Ishtar, who was known as Inanna in some cultures, was the Mesopotamian goddess of love and fertility. She was also associated with political authority and success in war. She emerged as the most widely revered deity in the Assyrian pantheon of gods, and it would have been impossible to visit an important city in the Assyrian Empire without finding a magnificent temple dedicated to Ishtar constructed at a prominent public location.

The fragment with the depiction of Ishtar was a standout find. But it was only one of the noteworthy relics and monuments recovered in Nimrud this year.

Revealing Assyrian History

The Penn Museum team also found several stone slabs in the palace that revealed the genealogy of Assyrian kings, leading up to Adad-Nirari III (he was descended from some of the most acclaimed Assyrian sovereigns). The ancient slabs featured the distinctive wedge-shaped cuneiform script used by the Assyrians, which shows the genealogy was indeed written nearly three thousand years ago.

Elsewhere on palace grounds, the researchers found two huge carved stone bases that would have supported soaring columns that once held up the palace’s roof. They also discovered fragments of ivory and ostrich eggshells , each of which can be connected to ancient Assyrian elite culture. Searching further inside the ruined palace, the team found a large stone basin in a throne room. Nearby were a pair of elevated stone tracks, which were built to move a portable heater that would have kept the room’s occupants comfortable on cold nights.

Near the location of what was once a 10-foot (three-meter) wide gateway leading in and out of the Temple of Ishtar, the archaeologists found a collection of brass door bands, still filled with the nails that were once used to attach them to the gateway’s wooden doors. On these bands were engravings of soldiers, horses and people carrying gifts, the first two likely designed to celebrate Assyrian military success and the latter showing worshippers paying their respects to the goddess.

The gateway itself was a significant discovery. It would have directly connected the Temple of Ishtar with another temple devoted to Ninurta, the Assyrian god of war (which explains the presence of military imagery on the brass bands). The gateway’s existence was long suspected, but never proven until now.

The Regeneration and Reemergence of Nimrud, a Mesopotamian Mecca

Nimrud was once the world’s most populated city. In 800 BC, when the Assyrian Empire was at the height of it power , more than 75,000 people called this renowned capital their home.

The Assyrian Empire, and Nimrud, were both destroyed by a coalition of former subject peoples in the late seventh century BC (the Assyrians were brutal and despised conquerors). But during the fabled city’s glory years huge, monumental structures dedicated to its leaders and gods were erected everywhere, which in modern times turned Nimrud into an archaeological mecca. The first excavations there took place in 1845, and the city’s site in northern Iraq was visited continuously by archaeologists and historical researchers from that point on, until the region degenerated into chaos during the war between Iraq and its allies and the Islamic State, which lasted from 2013 to 2017.

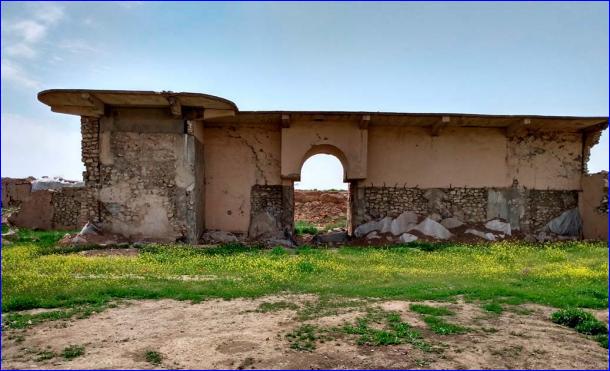

Fortunately, the city was retaken from the Islamic State a few years ago and is now guarded round-the-clock by the Iraqi Army. But tragically, the brutal occupiers destroyed approximately 90 percent of the structures that had been excavated by archaeologists in the past, using bombs and bulldozers. The Iraqi government is currently working to clear out all the rubble and reconstruct what was destroyed, while archaeologists from around the world continue to search for new ruins and artifacts in a sprawling ancient city that once covered a territory of 890 acres (360 hectares).

In the upcoming excavation season, the joint Iraqi and Penn Museum team of archaeologists will be concentrating on the area around the newly discovered gateway in the Temple of Ishtar. They will then venture into the space once occupied by the temple dedicated to Ninurta, a hero-god with roots in the famed Sumerian civilization that is recognized as Mesopotamia’s first great culture . Meanwhile the cleanup of the site as a whole will continue, as archaeologists and Iraqi authorities coordinate their efforts to restore Nimrud site to its former awe-inspiring state.

By Nathan Falde