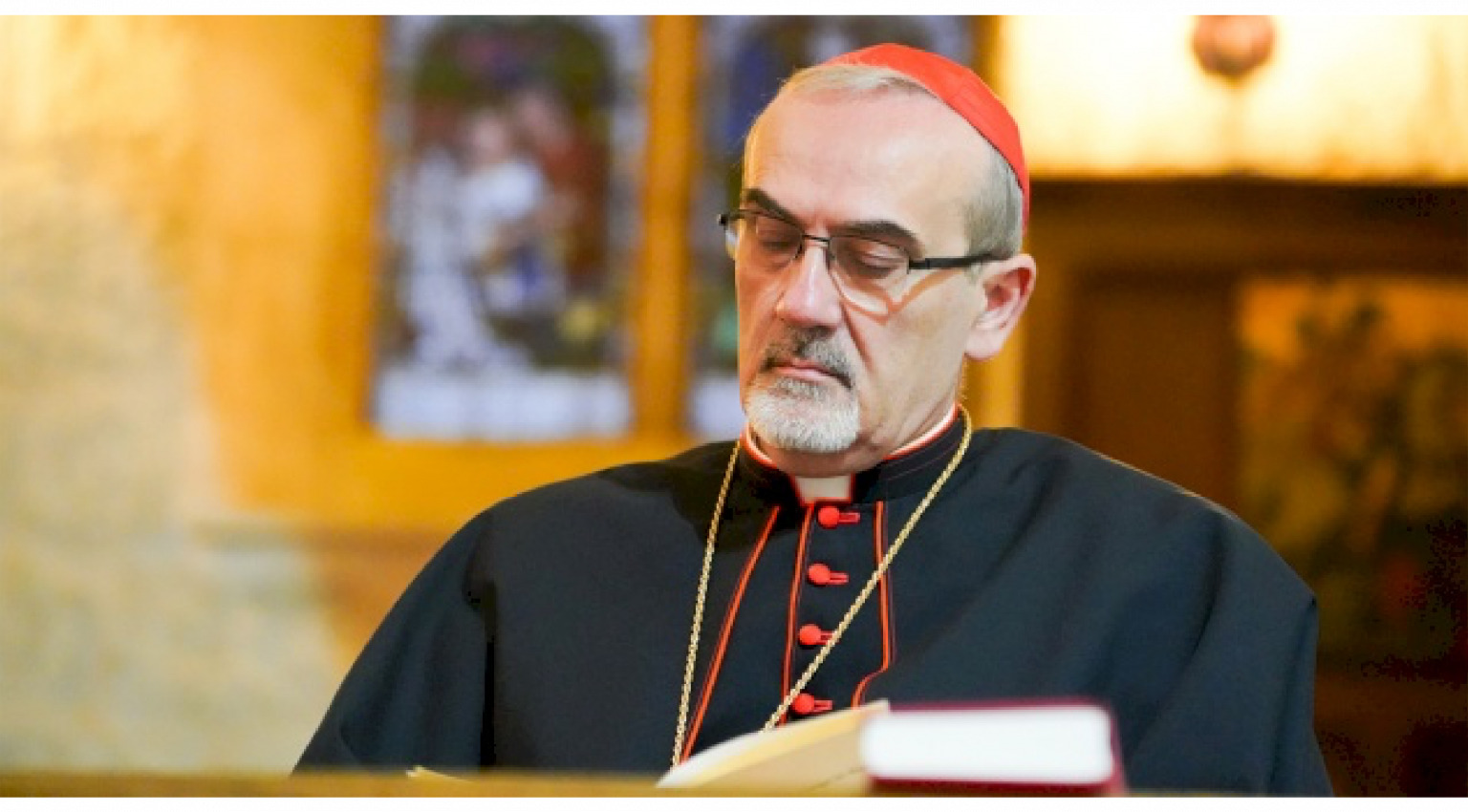

Ahead of the day of prayer and fasting for peace called by Pope Francis, Cardinal Pierbattista Pizzaballa, the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, shares his reflections on these 12 months of war, suffering and fear in the Middle East, which began on that tragic day on 7 October 2023.

Life in Jerusalem was not easy even before 7 October, but certainly, over the past year the days of the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem have been intense and frantic, filled with pastoral care, institutional relationships, and, inevitably, interactions with international media. “Undoubtedly, the part that bothers me the most is the press. It wastes a lot of my time”, jokes Cardinal Pizzaballa.

Your Eminence, a year has already passed since that terrible morning…

Yes, a terrible year. And we will remember it, together with Pope Francis and all the Churches of the world, with a day of prayer and penance, to keep our hearts free from all forms of fear and anger. And to bring to God through prayer our desire for peace for all humanity.

A month after the massacre of 7 October, you granted us a long interview. It deeply touched our readers because it was like emerging from the stunned silence into which that tragedy had plunged us… You also shared your personal feelings. “Everything will change,” you told us. What has actually changed? And what has changed for you and for Christians in the Holy Land?

Before 7 October 2023, political prospects were certainly completely different. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict, though latent, seemed to have entered a routine that was not particularly alarming, so much so that it did not constitute a priority on international diplomatic agendas. Interreligious dialogue followed its ordinary course, strengthened by Pope Francis’ travels and the Encyclical Fratelli Tutti. The Christian community actively carried out its pastoral activities. Now, all of this seems like a dead letter. Today, the Palestinian issue has resurfaced in such dramatic terms that it makes it even more difficult to resolve. Interreligious dialogue is going through a deep crisis. And the pastoral initiatives of the Christian community must be completely rethought in a new context, laden with distrust and misunderstandings. There is widespread hatred, both in language and physical, military violence, that we had never seen before. All of this cannot leave us indifferent. So, to answer your question: yes, a lot has changed, immensely. We must start talking about the future again, but keeping in mind that the wounds this conflict is leaving are numerous and deep. It has also been an incredibly difficult year for me. On the one hand, even if overwhelmed by this daily chaos, one must preserve and focus on spiritual life. And then, help guide the community in understanding the reasons for being here and their role. These are always very open questions because they do not have set answers that are valid over time.

In that November conversation, I remember thinking that in a few weeks, some sort of truce would be reached. We were wrong: we found ourselves commenting on the sixth month of war in an even more desperate atmosphere. There is a tragic paradox in this conflict: the longer it lasts, the more distant its resolution seems…

I don’t know if the conflict delays the conclusion, but it has certainly taken different turns. It is no longer concentrated on Gaza; it’s becoming a regional conflict, which everyone claims they want to avoid, but no one seems able to stop. I find it hard to believe that there could be a further expansion of the conflict into a full-out regional war in the Middle East, though the risk is there. Rather, I see another danger: the total lack of an exit strategy. All wars must have a political, not military, conclusion.

There is no political vision from any side…

Absolutely. They only talk about military strategies, not politics, in the belief that peace can only come with victory over the opponent. What will Gaza be like after? What will Lebanon be like? Is anyone discussing that? These, I believe, are the questions we should be asking. Questions that the international community should also be asking, to help find solutions. Otherwise, there will only be a general, mostly ignored, moral suasion towards pacification.

You’ve lived here for nearly thirty-five years…

Yes, I arrived here on 7 October (sic) of 1990.

And in all these years, you’ve seen many things. Yet, you’ve described this war as “the longest, the cruellest.” In this war, we’ve witnessed horrifying scenes from both sides; even the last remnants of humanity seem to have been lost. You know both societies well: what has happened? Why is there this unprecedented level of violence?

My impression is that something has broken in the soul of both societies. Maybe it was already cracked before, but now it’s fully broken. Both societies are traumatized. The Israeli society experienced 7 October as a small Shoah, while for the Palestinian society, the war in Gaza is a new Nakba. So, in both camps, there’s the reopening of deep wounds in the conscience of both peoples. These are gaping wounds that had marked the lives of both peoples forever and now reappear like menacing ghosts. This has unleashed fear. And fear can generate incredible violence because it is the fear of one’s very existence being at risk. From that fear, the violence and inhumanity we’ve witnessed this year have emerged: the refusal to recognize the existence of the other in order to preserve one’s own. You can already see it in the language being used, full of violence, inhumanity, and distrust. It’s always very important to look at the language.

However, on the Israeli side, up until 7 October, this fear was not apparent. In fact, thanks in part to a favourable economic season, society seemed to have removed the conflict from its consciousness. It’s no coincidence that the Israeli narrative begins firmly on 7 October, while for Palestinians, there’s also a 6, a 5, a 4, and so on. I mean, 2022 and 2023 had been very hard years in the West Bank…

True, Israeli society had convinced itself that the conflict with the Palestinians had been absorbed, assimilated. But here we come back to the role of politics, or rather, the absence of politics. Politics was unable to read reality and propose adequate solutions to a situation simmering beneath the surface, which instead exploded in the most violent, radical, and hateful way possible, catching everyone unprepared.

Unprepared, but also divided. The divisions within Israeli society, stirred up by Netanyahu’s judicial reforms, haven’t eased during the war. In fact, the protests have merged and grown alongside those over the handling of the hostage situation. The words of former Israeli President Reuven Rivlin, who warned of a return to the tribes of biblical Israel, come to mind. Does Israel risk winning militarily and losing politically?

It’s always a known fact that Israel, like many other societies, has its tribes. What has changed, if anything, is the type of tribes. Before, they were Ashkenazi, Sephardic, Russian, etc., but now they are secular, Orthodox religious, religious-nationalists, and so on. But I don’t think Israeli society is divided on the essential issues, primarily on the threat to its existence. There’s no substantial division over the military option. Perhaps there’s division over future prospects and the idea of the state, but not on the fundamental issues. What Israel will look like in a few years is too early to say. What is certain is that this war has carved a deep divide in the country’s political life. I think that, once the war is over, there will be profound changes. But what those changes will be and in what direction, is hard to predict today.

As for the Palestinians, the events of this past year seem to confirm what appears to be the historical fate of Palestinian society: the inability to produce authoritative leadership capable of pursuing a project of peace and coexistence with Israel…

The Palestinians are paying the price for many things. They are the scapegoat for many stories, for a macro-Middle Eastern politics that has always used them and never loved them — including by the Arab countries. And the Western countries, which have always supported them in words but never fully in action. And then, of course, they’re suffering from weak, divided leadership, often not up to the task. In the end, they’ve always been left alone. A people who have endured so much violence, from both outside and within.

Last year, in a lengthy interview with Vatican media, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas raised a point that hasn’t been sufficiently reflected on, despite its simple clarity: the reasons for the conflict are not only political but also, above all, anthropological and cultural — the insurmountable gap in customs and values between Arabs and Jews, most of whom came from Europe. The small Christian community that you lead has the advantage of not having an exclusive ethnic reference: there are Arabic-speaking Christians and Hebrew-speaking Christians. Can this be a laboratory for possible dialogue?

Conflicts are almost never purely political and military. There are always cultural, historical, and identity reasons at their root. That this conflict has an anthropological dimension is beyond question. There are two completely different worldviews, ideas of society, and notions of humanity. Just visit Ramallah and Tel Aviv to get a sense of that difference. They might meet on some issues. You’re right in saying that this important aspect hasn’t been sufficiently highlighted. The prospects here will never be one of integration but, at best, of respectful and civil coexistence. Living like in a condominium, where everyone remains themselves, with their own culture, customs, and identity. It’s difficult, I know, but it’s possible. Our small interethnic community, the Catholic Church, remains a small sign of this. Certainly, we will never set the standard, but our effort — because it’s difficult for us too to maintain this unity within — must remain a sign of a different way of living and relating. And it should also be one of the ways the Church makes a difference in this land, which is always so divided on everything.

Your Eminence, this year you have achieved a personal record, although a sad one, of being the first, and still the only, religious leader to enter Gaza. Could you tell us something about that experience, especially from the perspective of human relationships?

Yes, I managed to enter Gaza. And I hope to return. A shepherd’s duty is to be present, to be there with his flock. I wanted not only to be close to them but also to understand how to help them, to be useful. When I entered Gaza — and it was not easy at all — I found a terrible situation, a destroyed city, where the absence of demolished buildings made it impossible to even identify the streets, making orientation difficult. Total desolation. On the other hand, I found a living and moving community. They were surprised by my arrival, as was their parish priest, Father Gabriel, who had been outside Gaza on the morning of 7 October. I stayed for four days. Days of hardship and hope. What struck me most about the community is that I didn’t perceive a single word of resentment, hatred, or anger. Nothing. And this surprised me a lot because, humanly speaking, they had every reason in the world to be angry and frustrated. I deeply appreciated the presence and incredible work done by the nuns. I was particularly moved by the words of a young man I confirmed during my stay. The 7 October attack had been called “Operation Al Aqsa Flood” by Hamas, and he told me: “If that is the flood, we, the Christian community of Gaza, are the Ark, Noah’s Ark.” The Ark suspended on the waves of a sea of violence, with its bow aimed at the rainbow of peace.

The Church’s position is disarmingly simple: it stands with those who suffer, no matter which side they are on. Yet, this is hard to grasp. From this perspective, you’ve been a frequent target this year, pulled from one side to the other. Do you want to take this opportunity to address such criticisms?

When you hold a public role in such a polarized context, it’s inevitable to be a target. The important thing is that, when speaking, one tries to express not what others expect to hear but what one believes, in good conscience, is right and true. Mistakes are to be expected, as they are unavoidable in such a critical context: for example, sometimes excessive communication, or insufficient or incomplete. The important thing is to be honest: the Church must stand with those who suffer. Always. The Church cannot be neutral. I can’t go to my parishioners in Gaza, who are under bombardment, and say, “We are neutral.” However, while it’s true that the Church cannot be neutral, it’s also true that we cannot be part of the conflict. That would not only be wrong but also foolish in a context where, after 76 years of war, the faults of both sides do not cancel each other out but add up. In such a polarized environment, it’s not easy to be true, to have the courage to speak a word of truth, and also to know how to express closeness to those who suffer. It’s about keeping the dialogue open with everyone, with those who suffer, of course, but also with those who are the cause of the suffering. As a person and as an institution, I must remain a free reference point in every sense in this painful tangle of violence, hatred, exclusionary narratives, and rejection. I am not called to express the positions of the Palestinians, much less those of the Israelis. I must speak on behalf of the Church. And the Church’s voice has only one criterion: the Gospel of Jesus Christ. That is where we must start and where we must always return.

May I ask you a more personal question? I recall from our conversation 11 months ago that you emphasized the term “solitude.” You were referring mainly to the loneliness of truth in a context of hatred, but it was quite clear that you yourself were feeling the heavy burden of solitude in your role as head of the Catholics of the Holy Land. How have you lived through these past eleven months?

Let’s say that solitude is demanded by the role. My role requires it because solitude allows you to be free. And you are not truly free unless you maintain a certain emotional distance. That said, I am human, and of course, I feel the weight of it.

I imagine it must be especially hard for someone who, like a friar, has always lived in community…

Certainly. But solitude must be inhabited. Inhabited by prayer, by the relationship with the Lord, by the awareness of doing what is right, by continuous discernment, and also by relationships with the right people.

Before taking on the role of shepherd for Christians in the Holy Land, you played a vital bridging role between Christians and Jews, and you led Hebrew-speaking Christians. Have your relationships with the Jewish Israeli world changed in any way after 7 October 2023?

There have been several phases. At first, it was difficult. Especially for them. They had a great need for closeness, solidarity, affection, love. Which perhaps they did not entirely feel. But we also felt the need for their understanding of what had happened in the weeks and months following 7 October. Over time, the true friendships remained. We are certainly in a new phase of interreligious dialogue. It’s no longer a time for mere good intentions and polite pleasantries; we need to ground our dialogue in reality, which presents itself in all its dramatic nature. We have discussed and dialogued a lot about our common and difficult past, and that was necessary. But now, without forgetting the past, we must focus on the present, starting with the difficulties we face today. Beginning with trying to understand why, at this crucial moment in our relations, we have struggled to understand each other, to speak a common language. And especially on how to unite our efforts in the direction of peace. It can no longer be an academic or theoretical debate but must be immersed in the living reality that surrounds us.

You are also the shepherd of Christians in Jordan. And you have been there several times in recent months. How was 7 October experienced there?

Not well, I would say. Jordan saw continuous protests in the first months, some of them quite intense, in solidarity with the Palestinians of Gaza and against Israel. Let’s not forget that about 60 percent of Jordan’s population is Palestinian, and much of the Jordanian Christian community is also of Palestinian origin.

All media attention is now focused on the northern front with Lebanon and the dangers of war between Israel and Iran. Much less attention is given to the situation in the West Bank, which, politically, is the real core of the issue. You were recently in Jenin, the epicentre of violent clashes between the Israeli army and Palestinian militants…

Politically, the situation is complex and plays out on various fronts. The West Bank is certainly one of the most complicated. Since 7 October, the situation there has worsened in economic, political, and military terms. The ongoing incursions by Israeli settlers are creating a “no man’s land,” without rules or law, where whoever shoots first and hardest wins.

Narrowing the focus even more, everything looks to Jerusalem. Without peace in Jerusalem, there will never be peace in the entire Middle East. Years ago, you told me that “the war in Jerusalem is a real estate war, fought to seize every square meter”; meanwhile, the infiltration of Jews into the Old City and the eastern part continues without interruption…

That’s right. Jerusalem is the litmus test of the conflict, not only in the Holy Land but throughout the Middle East. Jerusalem is the heart of everything, for better or for worse.

The Knesset has formally shelved the two-state solution, and Netanyahu has called the Oslo Accords a mistake in Israel’s history. There is one expression that both Netanyahu and Sinwar share: they both claim exclusive jurisdiction “from the river to the sea,” leaving no space for the other. Does the “two peoples in two states” solution still have any practicability today?

There are problems that have solutions, and problems that don’t. Realistically, at this moment, there is no solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, whether it’s “two peoples in two states” or “two nations in one state” or any other imagined solution. We need new faces and new perspectives. And this is a problem not only for this land but for the entire Middle East, starting, after recent events, with Lebanon. We need to rethink the entire context broadly, and Jerusalem, which I repeat, is at the heart of the matter. The whole Middle East needs new leadership and new visions. Only after that can we discuss the arrangements most conducive to peace between peoples.

This year, you also travelled extensively in Europe and America. What was your perception of the Christian communities’ response to the ongoing conflict?

Unity in supporting the Christians of the Holy Land, but otherwise, much confusion, if not division. It’s difficult to understand the reasons for the conflict. After all, in other countries, politics also leads to polarization. Only Pope Francis’ voice rises to lament the crisis of humanity that pervades these sad times. And I say this without any partisan pride, but with much sorrow in my heart.

By Roberto Cetera | osservatoreromano