Residents of northern village of Biram that was destroyed decades ago send letter to Vatican ambassador in Jerusalem in hopes of having Benedict XVI use his diplomatic weight on Israeli officials to have village resettled

Associated Press

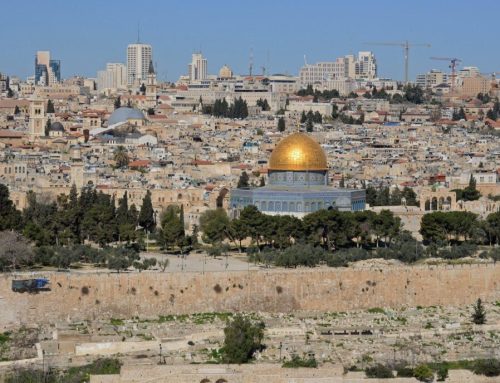

Displaced during war decades ago, the Christians of Biram have never given up their dream of returning to this destroyed village in the hills of northern Israel. They still hold Easter rites, weddings and funerals in a stone church, the only building left standing.

Now, they are pinning their hopes on Pope Benedict XVI, who is visiting the Holy Land in May. Biram’s former residents and their descendants, some 3,000 Catholics altogether, are asking their spiritual leader to speak for them. They were driven out of Biram during the 1948 war. Most Israeli leaders who dealt with Biram’s case refused their repatriation, fearing it would set a precedent for millions of Palestinian refugees seeking to return to former properties. But the villagers argue their case is different because their hamlet was bombed years after the war ended, and that a 1952 court case paved the way for them to return. “This pope must say the truth,” said parishioner Edmond Rawis, 79, pointing toward where his house once stood.

The villagers say they have written to the Vatican’s ambassador in Jerusalem, Archbishop Antonio Franco. The ambassador said he is aware of the issue, but has not received a letter and does not know whether the pope will discuss Biram with his Israeli hosts. Only Biram’s church, the cemetery and the ruins of an ancient synagogue are still standing. Descendants return here to worship, marry, baptize their children and bury their dead in crypts that eerily resemble homes. Biram’s Christians belong to the Maronite church, which prays in Aramaic but follows the pope in Rome. During the 1948 war, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians fled or were expelled from their homes, and their villages were either destroyed or left to deteriorate. Most fled to neighboring Arab countries, but some, like those of Biram, remained within Israel’s borders and became citizens. Some of Biram’s 1,000 residents left for nearby Lebanon, but most stayed within Israel’s newly created borders, mostly in the nearby Arab-Israeli village of Jish. For decades, the villagers have lobbied successive Israeli governments to return, meeting only rejection – except for a short-lived effort in the 1990s. Then, the Israeli government headed by Yitzhak Rabin offered restitution to a few of Biram’s descendants on a small chunk of their ancestral lands. As they tried to negotiate a better deal, Rabin was assassinated in 1995. But they say there’s a chance to revive their issue if the pope leans his significant diplomatic weight on officials here. In 2000, the pope’s predecessor, John Paul II, asked then-Prime Minister Ehud Barak to resettle them in Biram, villagers say they were told by local Catholic officials at the time. An Israeli Foreign Ministry official, Yigal Palmor, said the issue should be pursued in the country’s courts, and not through political lobbying.

In 1952, the high court ruled that the eviction from Biram was not “entirely legal,” but military authorities then retroactively issued eviction notices, according to historians. Biram residents argue that the ruling opens the door for their return. In 1953, Israeli warplanes bombed Biram in an attempt to discourage the villagers from returning. In the village’s graveyard, Biram’s dead are buried in crypts. Israeli authorities have not objected to their quiet repossession of the cemetery, said a villager, Kamel Yakoub. “It’s the liveliest place in Biram,” Yakoub said.