Zenit

Here are the “lineamenta,” or guidelines, for the Special Assembly for the Middle East of the Synod of Bishops, to be held Oct. 10-24 .

The theme for the synod is: “The Catholic Church in the Middle East: Communion and Witness. ‘Now the company of those who believed were of one heart and soul'” (Acts 4: 32).

* * *

PREFACE

The Acts of the Apostles, highlighting the communion and witness of Christians as followers of Jesus Christ, speaks in two passages of the sharing of goods. The first states: “and they devoted themselves to the Apostles’ teaching and fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers” (Acts 2: 42). Their way of life resulted from an intense unity: “and all who believed were together and had all things in common” (Acts 2: 44). The topic for the Special Assembly for the Middle East of the Synod of Bishops, to take place from 10 to 24 October 2010, is taken from the second passage: “Now the company of those who believed were of one heart and soul” (Acts 4:32). St. Luke gives two examples to illustrate this statement. The first is positive: Joseph called Barnabas, who sold a field he possessed “and brought the money and laid it at the apostles’ feet” (Acts 4:37). The other, a negative one, is an account of a couple, Ananias and his wife Sapphira, who agree to give only a portion of the proceeds of the sale of land and keep the rest for themselves. Their deceit was discovered and the dramatic punishment caused “great fear” in the ecclesial community (cf. Acts 5:1-11). These instances call upon Christians to live the ideal of communion and witness in a concrete manner, urging them to fulfill their task not half-heartedly but completely, to the point of being truly “one heart and soul” (Acts 4:32).

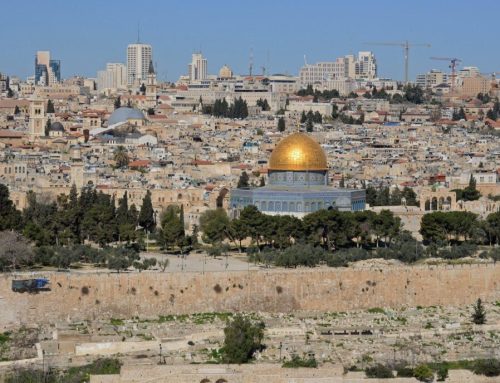

The great history of evangelization recounted in the Acts of the Apostles begins with the Christian community in the Holy Land. All Christians and people of good will look to this land made holy by the presence of the Lord Jesus, particularly at this time of preparation for the Special Assembly for the Middle East of the Synod of Bishops, which the Holy Father, Pope Benedict XVI convoked on 19 September 2009, during his meeting with the patriarchs and major archbishops of the Eastern Catholic Churches. At the same time, the Supreme Pontiff announced the topic of the synodal assembly: “The Catholic Church in the Middle East: Communion and Witness. ‘Now the company of those who believed were of one heart and soul'” (Acts 4:32). The Holy Father, who visited the Holy Land from 8 to 15 May 2009, readily acceded to the requests of many of his brothers in the episcopate to convoke a synodal assembly for the Middle East, whose purpose is to examine thoroughly the teachings in the Acts of the Apostles, to relive the experience of the early Church community in a more mature fashion and to render testimony in word and, above all, in deed, as the fruits of an authentically Christian life, for the glory of God the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, in the complex present-day situation in the countries of the Middle East. This faith is to nourish Christian hope, believing “against every hope” (Rm 4:18), because it rests not on human ability but a divine power. Consequently, faith and hope must lead to charity towards one’s neighbour, which has been particularly seen in the Catholic Church in the Middle East by the continual presence of Christians in this, their homeland, from the time of Jesus. Clearly, this love of neighbour is also manifested in the many valuable apostolic works with which the members of the Catholic Church bear witness to their faith and, at the same time, make a notable contribution to the integral development of society as a whole.

So as to exercise this vocation fully, the Holy Father, Pope Benedict XVI has requested the accustomed process be followed in preparing for this synodal assembly. Consequently, the Supreme Pontiff has asked the Pre-Synodal Council for the Middle East, made up of 7 patriarchs, representing the 6 patriarchal Churches and the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, 2 presidents from episcopal conferences and 4 heads of dicasteries of the Roman Curia, to compose the text of the Lineamenta, which is presently being published in 4 languages: Arabic, French, English and Italian. Each chapter of the document is followed by questions, whose purpose is to generate discussion throughout the Church of the Middle East. The responses to these questions are to be submitted to the General Secretariat of the Synod of Bishops by Easter, which all Christians will celebrate on a common date this year: 4 April 2010. As noted, the contents of these responses will serve as the basis for the Instrumentum laboris, the work-document for the synodal assembly, which the Holy Father, Pope Benedict XVI will present to the distinguished representatives of the Catholic episcopate of the Middle East, during his Apostolic Visitation to Cyprus in June, 2010.

We entrust the preparations for the Special Assembly for the Middle East to the intercession of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Mother of the Church and Most Pure Flower of the Holy Land. In Bethlehem, she gave Jesus to the world; in Nazareth, she raised him, and then followed him through the streets of Galilee and Judea to Jerusalem, a city sacred to Christians, Jews and Muslims. As a result of the witness of Christians, the celebration of this synodal assembly can also become a propitious occasion for greater dialogue with the Jews and Muslims and a deepening of communion with all people of good will in the Middle East.

Nikola ETEROVIĆ

Titular Archbishop of Cibale

General Secretary

Vatican City, 8 December 2009

INTRODUCTION

1. In a meeting with the Eastern Patriarchs and Major Archbishops on 19 September 2009, the Holy Father, following his pilgrimage to the Holy Land (8 – 15 May 2009), announced the convocation of a Special Assembly for the Middle East of the Synod of Bishops, to take place from 10 to 24 October 2010. This initiative concerns the “anxiety” of the successor of St. Peter “for all the Churches” (2 Cor 11:28) and is an important event demonstrating the interest of the Universal Church in the Churches of God in the Middle East. The Churches themselves in the region are invited to become particularly involved in this event so that it might indeed be a grace-filled happening in the life of Christians in the Middle East.

Pope Benedict XVI’s pilgrimages to the Holy Land (Jordan, Israel and Palestine) and Turkey (28 November -1 December 2006), with the many, significant speeches given on these occasions, provide special assistance in better understanding the Word of God and reading the signs of the times, so that we can thereby discern the vocation of our Churches and how to conduct ourselves as Christians.

A. The Aim of the Synod

2. The Special Assembly for the Middle East of the Synod of Bishops has a twofold goal: to confirm and strengthen Christians in their identity through the Word of God and the sacraments and to deepen ecclesial communion among the particular Churches, so that they can bear witness to the Christian life in an authentic, joyful and winsome manner. Our Catholic Churches are not alone in the Middle East. There are also the Orthodox Churches and the Protestant communities. This ecumenical aspect is basic, if Christian witness is to be genuine and credible. “That they may all be one, so that the world may believe” (Jn 17: 21).

3. Thus, communion has to be deepened at all levels: within the Catholic Churches in the Middle East themselves, among all Catholic Churches in the region and in relations with other Christian Churches and ecclesial communities. At the same time, we have to strengthen the witness we give to Jews, Muslims, believers and non-believers.

4. The synod also offers us the opportunity to assess the social as well as the religious situation, so as to give Christians a clear vision of the significance of their presence in Muslim societies (Arab, Israeli, Turkish or Iranian), and their role and mission in each country, and thereby prepare them to be authentic witnesses of Christ where they live. Accordingly, this involves reflecting on the current situation, which is a difficult one of conflict, instability and political and social evolution in the majority of our countries.

B. A Reflection Guided by Sacred Scripture

5. Our reflection will be guided by Sacred Scripture, which was written in our lands, in our languages (Hebrew, Aramaic or Greek) and in the cultural and literary contexts and expressions we hold as our own. The Word of God is read in our Churches. The Scriptures have come to us through our ecclesial communities, having been handed down and meditated upon within our Sacred Liturgies. They cannot be ignored as a reference point, if we are to discover the meaning of our presence, our communion and our witness in the current situation in our countries.

6. What does the Word of God say to us here and now, to each Church, in each of our countries? How does God’s loving Providence reveal itself to us in both the favourable and challenging situations of our daily life? What is God asking of us at this time: to remain so as to commit ourselves to these events which are under the care of Providence and divine grace? Or are we to leave?

7. Therefore, it is a matter – and this is one of the aims of the Special Assembly – of rediscovering the Word of God in the Scriptures, addressed to us today. The Word of God speaks to us in the present and not merely in the past, and explains to us what is happening around us, just as the Word did to the two disciples of Emmaus. This discovery comes about primarily from reading and meditating upon Scripture, whether done individually, in families or living communities. What is essential, however, is that this reading guide the choices we make each day in our personal, familial, social and political lives.

QUESTIONS

1. Do you read Scripture individually, in your family or in living communities?

2. Does this reading inspire the choices you make in family, professional and civic life?

CHAPTER I

THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE MIDDLE EAST

A. The Situation of Christians in the Middle East

1. An Historical Sketch: Unity in Diversity

8. The Catholic Churches in the Middle East, like every Christian community throughout the world, trace their roots to the first Christian Church of Jerusalem, made one by the Holy Spirit on the day of Pentecost. In the 5th Century, after the Councils of Ephesus and Chalcedon, the Church underwent divisions principally over christological issues. The first schism resulted in the Churches known today as the “Apostolic Assyrian Church of the East” (which used to be called Nestorian) and the “Eastern Orthodox Churches,” namely the Coptic, Syrian and Armenian Churches, which used to be called monophysite. Oftentimes, these divisions also reflected politico-cultural factors, as highlighted by the Eastern medieval theologians who belonged to the three great traditions known as “Melkite”, “Jacobite” and “Nestorian”. All maintained that this division had no dogmatic basis. Afterwards came the Great Schism of the 11th Century which separated Constantinople from Rome and subsequently the Orthodox East from the Catholic West. These divisions still exist today in the various Churches of the Middle East.

9. In the wake of these divisions and separations, periodic attempts were made to re-establish the unity of the Body of Christ. This ecumenical effort gave rise to the Eastern Catholic Churches: Armenian, Chaldean, Melkite, Syriac and Coptic. At first, these Churches were tempted to indulge in polemics with their Orthodox Sister-Churches, however, at the same time, they have often become ardent defenders with them of the Christian Middle East.

10. The Maronite Church has remained united to the Universal Church and throughout its history has not experienced any internal ecclesial divisions. The Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem, established at the time of the Crusades, was re-established in the 19th Century, as a result of the continual presence of the Franciscan Fathers, especially in the Holy Land, from the beginning of the 13th Century.

11. Today, seven Catholic Churches exist in the Middle East, the majority of which are Arabic or have assumed an Arabic character. Some of them are also present in Turkey and Iran. All are culturally distinct and, consequently, have unique liturgical traditions – Greek, Syriac, Coptic, Armenian or Latin – which constitute their wonderful richness and complementarity. They are in one communion with the Universal Church, gathered around the Bishop of Rome, the successor of St. Peter, coryphaeus of the apostles (hâmat ar-rusul). Diversity is the basis of their richness, a richness which can be impoverished by an excessive attachment to rite and culture. Collaboration among the faithful proceeds normally and naturally at every level.

2. Apostolicity and Missionary Vocation

12. Our Churches are apostolic in origin and our countries have been the cradle of Christianity. The Holy Father, Pope Benedict XVI, said on 9 June 2007 that they are the living guardians of our Christian origin.

13. In being apostolic, our Churches have the special mission to bring the Gospel to the whole world. Throughout history, this apostolic fervour has accounted for several of our Churches in Nubia and Ethiopia, in the Arabian Peninsula, in Persia, and in India and as far as away as China. Today, in some cases, there are signs that this evangelical ardour has grown cold and the flame of the Spirit dampened.

14. Our history and culture puts us in close contact with hundreds of millions of people, culturally as well as spiritually. Our responsibility is to share with them the Gospel message of love, which we have received. At a time when entire peoples have lost their way and are looking for a glimmer of hope, we can give them the hope which is in us, because of the outpouring of the Spirit in our hearts (cf. Rm 5:5).

3. The Role of Christians in Society, Despite their Small Number

15. Our Arab, Turkish and Iranian societies, in spite of their differences, share common characteristics. Traditions and a traditional way of life are prevalent, especially regarding the family and education. Confessionalism characterises relations among Christians themselves as well as those with non-Christians and profoundly affects attitudes and behaviour. Religion can give rise to divisions, one from the other.

16. Modernity is increasingly pervasive in society. Access to worldwide TV channels and the Internet has led to both new values and the loss of values in civil society and among Christians. In response to this situation, Islamic fundamentalist groups are becoming widespread. Those in power react authoritatively with strict control of the press and media. The majority of people, however, long for true democracy.

17. Although Christians are a small minority in almost every part of the Middle East (with the exception of Lebanon) – ranging from less than 1% (Iran, Turkey) to 10% (Egypt) – they are still active, dynamic and penetrating. The danger lies in their isolating themselves out of fear of others. Our faithful need to be strengthened in their faith and spirituality and the social bonds and solidarity among them re-forged. However, this must be done without falling into a ghetto mentality. In addition, education is our greatest investment. Our Churches and schools need to do more to help the least fortunate.

B. The Challenges Facing Christians

1. The Political Conflict in the Region

18. Political conflicts in the region have a direct influence on the lives of Christians, both as citizens and as Christians. The Israeli occupation of the Palestinian Territories makes daily life difficult with regard to freedom of movement, the economy and religious life (access to the Holy Places is dependent on military permission which is granted to some and denied to others on security grounds). Moreover, certain Christian fundamentalist theologies use Sacred Scripture to justify Israel’s occupation of Palestine, making the position of Christian Arabs even more sensitive.

19. In Iraq, the war has unleashed evil forces within the country, religious confessions and political movements, making all Iraqis victims. However, because Christians represent the smallest and weakest part of Iraqi communities, they are among the principal victims, with world politics taking no notice.

20. In Lebanon, Christians are deeply divided at a political and confessional level, without a commonly acceptable plan of action. In Egypt, the rise of political Islam, on the one hand, and the disengagement of Christians from civil society on the other, lead to intolerance, inequality and injustice in their lives. Moreover, this Islamisation also penetrates families through the media and school, leading to an unconscious change in attitudes which is Islamic in character. In many countries, authoritarianism or dictatorships force the population – Christians included – to bear everything in silence so as to safeguard what is essential. In Turkey, the idea of “secularity” is currently posing more problems for full religious freedom in the country.

21. This situation of Christians in various Arab countries has been described in paragraph 13 of the Catholic Patriarchs’ 10th Pastoral Letter (2009). Its conclusion disapproves a defeatist attitude: “Confronted by these different realities, some remain strong in their faith and their commitment in society, sharing common sacrifices and contributing to the overall social plan. Others, in contrast, are discouraged and have lost all confidence in their society and in its capacity to accord them the same equal status as other citizens, leading to their abandoning all engagement, withdrawing into their Churches and institutions, and living in isolation and devoid of interaction with society.” [2]

2. Freedom of Religion and Conscience

22. In the Middle East, freedom of religion customarily means freedom of worship and not freedom of conscience, i.e., the freedom to change one’s religion for belief in another. Generally speaking, religion in the Middle East is a social and even a national choice, and not an individual one. To change religion is perceived as betraying a society, culture and nation, founded largely on a religious tradition.

23. Conversion is seen as the fruit of a proselytism with personal interests attached and not arising from authentic religious conviction. Oftentimes, the conversion of Jews and Muslims is forbidden by State laws. Christians, though also subjected to pressure and opposition from families and tribes – even if less severely – remain free to change their religion. Many times, the conversion of Christians results not from religious conviction but personal interests or under pressure from Muslim proselytism, particularly to be relieved from obligations related to family difficulties.

3. Christians and Developments in Contemporary Islam

24. In their previous Pastoral Letter, the Catholic Patriarchs of the Middle East said: “The rise of political Islam, from the 1970’s onwards, is a prominent phenomenon which affects the region and the situation of Christians in the Arab world. This political Islam includes different religious currents which seek to impose an Islamic way of life on Arab, Turkish and Iranian societies and on all those who live in them, Muslim and non-Muslim alike. For them, the cause of all ills is the neglect of Islam. The solution is therefore a return to original Islam. Hence the slogan: ‘Islam is the answer’… In pursuit of this goal, some do not hesitate to resort to violence.” [3]

This attitude, though primarily concerning Muslim society, has an impact on the Christian presence in the Middle East. These extremist currents, clearly a threat to everyone, Christians and Muslims alike, require a treatment in common.

4. Emigration

25. The emigration of Christians and non-Christians from the Middle East, a phenomenon which began at the end of the 19th Century, chiefly arose for political and economic reasons. At the time, religious relations were not ideal. However, the “millet” system (of ethnic-religious communities) guaranteed a certain protection to Christians within their communities, though not always preventing conflict which was both tribal and religious in nature. Today, emigration is particularly prevalent, because of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the resulting instability throughout the region and culminating with the war in Iraq and the political instability of Lebanon.

26. The plan of international politics, oftentimes ignoring the existence of Christians, further creates a major cause for emigration. Likewise, the current political situation in the Middle East makes difficult an economy which can provide an acceptable standard of living for the whole of society. Where certain measures can be taken to reduce emigration, its roots lie in prevailing political realities, which should be the focus of action and the area of engagement for the Church.

27. Another approach to limit emigration might be to make Christians better aware of the significance of their presence in a given country, where each Christian is to bear the message of Christ, a message which is to be proclaimed despite difficulties and persecution. In the Gospel, Christ states: “Blessed are you when men revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account. Rejoice and be glad, for your reward is great in heaven, for so men persecuted the prophets who were before you” (Mt 5: 11-12). This then is the ideal which, with Christ’s help, we must achieve.

5. The Immigration of Christians to the Middle East from the World Over

28. Hundreds of thousands of immigrant workers come to the Middle East from the world over: Africans, from Ethiopia and those primarily from Sudan, and Asians, especially from the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan and India. Generally speaking, these immigrants are women engaged in work as domestic servants so they can give their children an education and a better life. Oftentimes, these women (and men also) are subject to social injustice, exploitation and sexual abuse, either by the State which receives them, the agencies which provide passage for them or their employers.

29. These people are a pastoral responsibility from both a religious and social perspective. Oftentimes, these immigrants find themselves in tragic situations where the Church is unable to do much. Likewise, educating our Church members in the Church’s social teaching and social justice is urgently needed, if we are to avoid attitudes of superiority or contempt. Furthermore, international laws and accords are not respected.

C. The Christian Response in Daily Life

30. The conduct of Christians in our Churches and societies, in the face of the aforementioned challenges, is varied:

— many believing and committed Christians accept and faithfully live their faith in their public and private lives;

— some “lay” Christians, as witnessed in the present-day in our different countries, have been deeply engaged in public life in founding political parties, especially on the Left, or becoming members of a particular party, but oftentimes sacrificing their faith;

— other Christians exercise a traditional faith in devotions and external practices, which sometimes have no influence on their practical life or their scale of values. On the contrary, they submit to the standards and pragmatic values of their societies, even, at times, in contradiction to the Gospel, adopting the struggles of their society as their own, and distinguishable only by their exterior religious practices or the feasts they celebrate or their Christian name; and

— finally, still other Christians, seeing themselves in a position of weakness, because of the small size of their community in a Muslim-dominated society, give way to fear and become anxious and concerned about the violation of their rights.

31. The manner of living the faith is directly related to proper understanding what it means to be a member of the Church. A deep faith is the basis for a secure, committed sense of belonging, where, on the contrary, a superficial faith leads to a casual sense of belonging. In the first case, membership is true and authentic; believers participate in the Church’s life and exercise every aspect of their faith. In the second case, membership is “confessional only”.[4] In this case, believers demand that their Church meet every aspect of their material and social needs, leading to “extreme reliance” and passivity.[5]

32. Consequently, personal conversion among Christians – starting with Pastors – is essential by returning to the Gospel spirit, so that our lives can become a witness to the love of God, which is expressed concretely towards each and every person, in witnessing to the Risen Christ: “With great power the apostles gave their testimony to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus” (Acts 4:33); and in abandoning our selfishness, rivalries and personal weaknesses.

33. The consecrated life is present in our countries in various ways. The contemplative aspect, if lacking, is to be pursued in the consecrated life. Monks and contemplatives have, as their primary mission, prayer and intercession for society in the following areas: greater justice in politics and the economy; increasing solidarity and respect in family relations; greater courage in denouncing injustices; and more honesty, so as not to be dragged into civic quarrels or the pursuit of personal interests. Such are the ethical goals of Pastors, monks, contemplatives, consecrated persons and educators, who must set an example in our institutions (schools, universities, social centres, hospitals, etc.), so that our faithful might themselves be true witnesses of the Resurrection in society.

34. The formation of our clergy and faithful and our homilies and catechesis must provide believers with an authentic sense of their faith, making them aware of their role in society in the name of their faith. They must be taught to seek and see God in all things and in everyone, striving to make him present in our society and our world by the practice of personal and social virtues: justice, honesty, righteousness, hospitality, solidarity, openness of heart, moral purity, fidelity, etc.

35. To this end, a special effort must be made to search out and form the “key persons” needed in the aforementioned endeavour -priests, consecrated women and men, lay men and women- so that they can be, in our societies, true witnesses of God the Father, of the Risen Jesus and of the Holy Spirit, poured out upon his Church to comfort the brothers and sisters in these difficult times and to contribute to building the civitas.

QUESTIONS

3. What are the Churches doing to support and encourage vocations to the religious and contemplative life?

4. How can we contribute to the improvement of the social environment in the various countries in our region?

5. What is your Church doing to assist, with the necessary critical eye, in dealing with contemporary ideas in your societies?

6. How can respect for freedom of religion and freedom of conscience be increased?

7. What can be done to stop or slow the emigration of Christians from the Middle East?

8. How can we follow and stay in touch with Christian who have emigrated?

9. What should our Churches do to teach the faithful respect for immigrants and their right to be treated with justice and charity?

10. What is your Church doing to provide pastoral care for Catholic immigrants and to protect them against abuse and exploitation by the State (police and prison officers), by agencies and employers?

11. Do our Churches work to train Christian executives to contribute to the social and political life of our countries? What could they do?

CHAPTER II

ECCLESIAL COMMUNION

A. Introduction

36. The divine life within the mystery of the Holy Trinity is the foundation and model for Christian communion. God is love (cf. 1 Jn 4:8); the relations between the divine persons are relations of love. Thus, the communion of all members of the Church, the Body of Christ, is based on relations of love: “As you, Father, are in me and I am in you, may they also be in us” (Jn 17: 21). This means living together as one, within each of our Churches, the very communion of the Holy Trinity. The life of the Church and the Churches of the Middle East must be a communion of life in love, according to the model of the union of the Son with the Father and the Spirit

37. Jesus recommended this unity of life to us, using the example of the vine and the branches (cf. Jn 15:1-7). St. Paul further developed this reality of the Christian life with the analogy of the unity of the body in the plurality of its members (cf. 1 Cor 12:12-21). Therefore, every Church bases its communion of life on the fact that each member of the Church is, through Baptism, a member of the Body of Christ, who is the Head. Consequently, communion among the Churches or within the same Church consists in an awareness that each person is a member of the Body, whose Head is Christ. Christ is the Head, and each member must be worthy of the Head to whom each is intimately associated.

B. Communion within the Catholic Church and among the Various Churches

38. This communion within the Universal Church is manifested in two ways: firstly, communion in the Eucharist; secondly, communion with the Bishop of Rome, successor of St. Peter and Head of the whole Church. The Code of Canons for the Eastern Churches has codified in law this communion of life in the one Church of Christ. The Congregation for the Eastern Churches and the various Roman Dicasteries are likewise at the service of this communion.

39. On the level of the faithful, our schools and institutes of higher education, as well as charitable institutions like hospitals, orphanages and homes for the aged, welcome all Christians without distinction. In towns, the Catholic faithful of various Churches often frequent the Churches nearest to them, while remaining faithful to their confessional community where they receive the sacraments (Baptism, Confirmation, Marriage, etc.).

C. Communion among Bishops, Clergy and the Lay-Faithful

40. Communion among the various members of the same Church or Patriarchate is based on the model of communion with the Universal Church and the Successor of St. Peter, the Bishop of Rome. At the level of the Patriarchal Church, communion is expressed by a synod which gathers the bishops of a whole community around the Patriarch, the Father and Head of his Church. In an eparchy, the communion of the clergy, consecrated persons and the laity is centred around the bishop. Prayer, the Eucharistic Presence and listening to the Word of God are moments which unify the Church and bring it back to what is essential, namely the Gospel. The bishop has the responsibility to see that everything proceeds in harmony, despite moments of weakness.

41. This grace is communicated by the bishop to every pastor of a parish or congregation of believers, each of which has stronger and weaker members. Despite their limitations, they remain instruments in the hands of God, who has entrusted to them a treasure in earthen vessels (cf. 2 Cor 4:7). He makes them instruments of his grace: “for whenever I am weak, then I am strong”(2 Cor 12:10).

42. This implies, however, that the ministers of Christ and those who seek to follow him more closely have a grave responsibility in the community to not only shepherd the Church of God locally, [6] but even more guide it spiritually and morally. They are to be models and examples for others. The community expects them concretely to live the values of the Gospel in an exemplary fashion. Not surprisingly, the faithful expect of them (bishops, priests, monks and nuns) a greater simplicity of life, a real detachment from money and worldly goods, a splendid practice of chastity and a transparent moral purity. The faithful are seriously scandalized, when this is not the case.

43. Furthermore, the attitude of the two apostles, James and John, who asked Jesus to grant them the first places at his right and his left,[7] can still be detected, posing difficulties among the brethren. Instead of coming together to face difficulties in common, we sometimes argue among ourselves, counting the number of faithful in our Churches to ascertain who is the greatest. This spirit of rivalry destroys us. Instead, emulating each others’ good practices in spiritual and pastoral service can stir our creativity in serving others. Consequently, emulation of what is best in our services must be encouraged. At the same time, our Churches, like all Churches in the world, are in need of continuous purification. This Synod can provide the occasion for a sincere examination of conscience to ascertain, on the one hand, the strong points for promotion and development, and, on the other, the weaknesses to be courageously faced and corrected.

44. We need to rediscover the model of the primitive Christian community: “Now the company of those who believed were of one heart and soul, and no one said that any of the things which he possessed was his own, but they had everything in common. And with great power the apostles gave their testimony to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus, and great grace was upon them all. There was not a needy person among them.” (Acts 4:32-34).

45. The apostolic associations and movements, originating locally and elsewhere as well as those from the world over, must adapt themselves to the mentality and approach to life which the tradition of the welcoming Church and country have to offer. This demands a spirit of humility in obeying the bishop and educating oneself in the traditions, culture and, above all, the language of the country. In their praiseworthy undertakings, certain international movements, need to become more a part of our societies, yet without sacrificing their specific charism.

QUESTIONS

12. What does communion in the Church mean?

13. How is communion manifested among the various Churches of the Middle East and between them and the Holy Father?

14. How can relations among the various Churches be improved in the areas of religious, charitable and cultural activity?

15. Does the attitude of “Church people” concerning money pose a problem for you?

16. Does participation of the faithful of your Church in celebrations of other Catholic Churches pose a problem for you?

17. How can relations of communion among the various people in the Church be improved: between bishops and priests, people in consecrated life, lay-people?

CHAPTER III

CHRISTIAN WITNESS

46. A living faith bears abundant fruit: a faith without works is a dead faith (cf. Jas 2: 17). Our Churches are actively involved in many activities and projects, many youth movements, many educational and charitable institutions, etc. Sometimes these activities are effective in a practical sense, but not always bearing witness to the selfless love demanded by the Gospel.

A. Witnessing to the Gospel within the Church: Catechesis and Works

47. Ordinary evangelisation takes place in homilies at the Eucharistic celebration or the administration of the sacraments. It also occurs in the catechesis given in schools and parishes or “Sunday schools” to pupils in State institutions who have no Christian religious education. Catechists are to be well-trained and models of Christian living for the young (regrettably, priests are less involved in catechetical work). To a lesser degree, some catechesis can also be done through magazines, books and the internet. Biblical and theological training centres exist everywhere, not to mention universities and the international centres, located in Jerusalem and elsewhere.

48. In our countries, more than in the rest of the world, Sacred Scripture should occupy a central place and many biblical passages committed to memory. A good knowledge of one’s ecclesial tradition is essential as well as a knowledge, free of prejudice, of those with whom we live – Muslims or Jews – not to mention any objections they might raise concerning Christianity, so as to be better able to explain the Christian faith.

49. On civic issues in society, the Christian point of view should be stated clearly, soundly and intelligently. The young and the faithful should be taught to work together in solidarity with the poorest of the poor and with a sincere love towards everyone, Christians and non-Christians alike, instructing them to work for the common good of society as a whole.

50. The new means of communication, a very effective tool in witnessing to the Gospel – the internet (especially for young people), radio and TV – are too little utilized by us. Two Catholic media existing in Lebanon are noteworthy: “The Voice of Charity” (Sawt al-Mahabba) and TéléLumière/Noursat, which is broadcast throughout the Middle East and beyond. These and other Catholic information centres in our various countries deserve greater support.

51. Living in places abounding in all kinds of conflicts, young people are to be catechised, strengthened in their faith and enlightened by the commandment of love, so that they can make a positive contribution. What does it mean to love one’s enemy? How is this to be lived? How can one overcome evil with good? Christians need to be encouraged to participate in public life with the light, force and gentle character of their faith. Given the many divisions arising from religion, family and political clans, young people have to be trained to go beyond these barriers and internal hostilities to see the face of God in every person, so as to work together and build an all-inclusive, shared civic order. This must be the emphasis in our catechesis, especially in our Catholic schools, which are preparing young people to build a future based not on conflicts and instability but on collaboration and peace.

52. At the same time, the Church’s activity is seen in a great number of social works: clinics, hospitals, housing for orphans, the elderly and people with learning difficulties, etc. In these areas, the lay-faithful exercise an essential and not merely ancillary role. In some places these social works occasionally run the risk of becoming the source of confessional rivalry. Churches need to work together to avoid unnecessary duplication in some sectors or leaving others unattended.

B. Witnessing Together with other Churches and Communities

53. The real but imperfect bonds of communion existing between the Catholic Church and other Christian Churches and ecclesial communities are based on faith in the Crucified and Glorified Christ and the Sacrament of Baptism.[8] Relations, which are generally good and amicable, can be classified in two categories:

— on the individual level of friendships or collaboration between Churches, bishops, priests or the lay-faithful; and

— on the community level, when bishops from the same town meet regularly to deal with pastoral, social or political issues.

54. On the parish level, relations between priests are generally amicable, yet not without occasional rivalries or criticisms. When considering the Churches, two difficulties need to be pointed out.

One has to do with pastoral matters. Some non-Catholic Churches and ecclesial communities demand, in the case of mixed marriages, the re-baptism of the Catholic party. Another pastoral difficulty arises from the “evangelical sects” which proselytise and increase divisions between Christians.

The second difficulty is historical and inherent to the Holy Land, where the status of the Holy Places is subject to status quo arrangements. At the two great Christian shrines of the Holy Sepulchre and the Basilica of the Nativity, relations can sometimes be strained.[9]

55. Ecumenical dialogue takes place through the Middle East Council of Churches (the “Faith and Unity Committee”), which brings together four groupings: Greek Orthodox; Eastern Orthodox (the Coptic, Syriac and Armenian Churches); Catholics with the six Patriarchal Churches and the Latin Church; and Protestants (Anglicans, Lutherans, Presbyterians and other denominations). This Council represents practically all the Christians in the Arab world. With its several committees (faith, theological institutes and seminaries, justice and peace, youth, etc.), the Council performs an ecumenical task which instils new energy into the Church and a capacity to meet and respect others.

56. Furthermore, the Holy See carries out a fertile and fruitful theological dialogue in common with all the Orthodox Churches and a separate dialogue with the whole family of Eastern Orthodox Churches, in which the Catholic Churches of the Middle East also take an active part. From time to time, the Pro Oriente Foundation of Vienna gathers together the Catholic and Orthodox Churches of the region for theological and ecumenical reflection.

57. Catholic schools welcome all Christians. With parental consent, Orthodox pupils can receive the sacraments of Reconciliation and the Eucharist. Proselytism is never allowed. Orthodox pupils are invited to know their Church and to remain faithful to it. Numerous shared social projects exist, initiated and managed by the faithful themselves.

58. Shared pastoral projects are discussed by the Council of Catholic Patriarchs of the Middle East and the Orthodox Patriarchs of Lebanon and Syria on basically four issues: mixed marriages between different Christian confessions, First Communion, a communal catechism and communal dates for Christmas and Easter. Agreements have been reached on the first three issues. Book 6 of the communal catechism has been issued for Grade 6 in elementary schools. The question of a communal date for Christmas and Easter, dealt with by the Middle East Council of Churches, is facing insurmountable obstacles (of discipline, of tradition, etc.). The great desire of the faithful in all Middle Eastern countries, however, is to be able eventually to celebrate these two feasts together.

59. Academically speaking, collaboration exists among the theological universities, faculties or institutes. The study of the Syriac and Arabic religious heritage, engendering a genuine interest within both academic institutions and the hierarchies alike, holds great promise and can be a source of spiritual enrichment. Returning to a shared Tradition can also be an excellent way to become closer theologically. Furthermore, the Christian heritage of the Arabic language, when given due academic consideration, is of genuine assistance in cultural and religious dialogue among Christians and in interreligious dialogue with Muslims.

60. The Liturgy promises to be an area of regular collaboration between Catholics and Orthodox. Many desire a liturgical renewal which is grounded in Tradition and cognisant of modern sensitivities and current spiritual and pastoral needs. As far as possible, such work needs to be collaborative undertaking.

C. Special Relations with Judaism

61. Given the political conflict between the Palestinian and Arab world, on the one hand, and the State of Israel, on the other, dialogue has developed very little in the Churches of the region. Relations with Judaism are the prerogative of the Churches in Jerusalem.[10] A number of associations for Jewish-Christian dialogue exist in Palestine and Israel. Similar initiatives in dialogue also involve Jews, Christian and Muslims, the most important of which is the “Interreligious Council of Religious Institutions”, dating back to 2001 (including the Chief Rabbinate, the Chief qādi and the Minister of Waqf, and the thirteen Patriarchs or Heads of Churches in Jerusalem). Of particular importance is the dialogue between the Holy See (also including participants of local Churches) and the Chief Rabbinate of Israel.

62. Beginning with its second Pastoral Letter (1992), the Council of Catholic Patriarchs of the Middle East has expressly spoken on relations with Judaism. In its last Letter, the tenth (2009), the Council stated: “These relations are a question which concerns Christian Arabs and the whole Arab world. It is why they have to be considered at three levels: human, religious and political.

“On the human level, every human person is a creature of God. On this level of encounter, each of us sees the face of God in others in recognising their dignity and giving them respect, no matter what their religion or nationality.

“On the religious level, religions are invited to meet, engage in dialogue and act to bring people together, especially in times of crisis and wars […] The role of the religious leader in every religion is difficult, especially when hostility continues between two parties […] Our societies need sincere religious leaders, servants of their people and humanity, who see that the essentials of religion in every circumstance are adoring God and respecting all God’s creation.

63. “On the political level, this relation is once again marked by a situation of hostility between the Palestinian and Arab world, on the one hand, and the State of Israel [worsened by religious conceptions], on the other. Hostility is due to Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian Territories and some Lebanese and Syrian territory.”[11] On this level, the political leaders concerned, with help from the international community, have the responsibility to make the necessary decisions in accord with the resolutions of the United Nations.

64. The Holy Father, Pope Benedict XVI stated this clearly on his Apostolic Visit to the Holy Land, in two welcoming ceremonies. In Bethlehem, on 13 May 2009, he stated: “Mr. President, the Holy See supports the right of your people to a sovereign Palestinian homeland in the land of your forefathers, secure and at peace with its neighbours, within internationally recognised borders.” [12] And during his discourse at Ben Gurion Airport in Tel Aviv, on 11 May 2009, he expressed the desire that “both peoples might live in peace in a homeland of their own, within secure and internationally recognized borders.” [13]

65. As Christians, our responsibility is to deploy every peaceful means to achieve peace with justice. Our mission is also to make a constant distinction between religion and politics. Pope John Paul II pointed out, “No peace without justice and no justice without forgiveness”.[14] We have to learn to forgive, without ever tolerating injustice.

66. Working to create groups of friendship and reflection for the promotion of peace among Jews, Muslims and Christians is an essential task and an eminently Christian one. As Christ destroyed the wall that separated Jews from Greeks by taking evil upon himself, in his own flesh (cf. Eph 2:13-14), so it is our responsibility to bring down the wall of fear, mistrust and hatred through our friendship with Jews and Muslims, Israelis and Palestinians.

67. On the theological level, according to the teaching of Nostra aetate, no. 4, the religious bond between Judaism and Christianity, based on the inherent link between the Old and New Testaments, needs to be explained to our faithful to prevent political ideologies from spoiling relations. A distinction between politics and theology needs to be carefully done. At the same time, the Bible should never be used for political purposes nor politics for theological ends.

D. Relations with Muslims

68. Relations between Christians and Muslims have to be based on two principles. On the one hand, both must be seen to be citizens of the same country and homeland, sharing the same language and culture, not to mention the same fortunes and misfortunes of our countries. On the other, Christians must see themselves as members of the society in which they live and working on its behalf as witnesses of Christ and the Gospel. Oftentimes, relations can be difficult, mainly because Muslims frequently mix religion and politics, putting Christians in a precarious situation of being considered as non-citizens.

69. On 28 October 1965, during the Second Vatican Council, the Church declared to the world its position in relation to Islam: “The Church regards with esteem also the Muslims. They adore the one God, living and subsisting in himself; merciful and all-powerful, the Creator of heaven and earth who has spoken to men.” [15]

70. Our responsibility, therefore, is to work, in a spirit of love and loyalty, to establish equality for every citizen on all levels – political, economic, social, cultural and religious – in harmony with the constitutions of the majority of our countries. In faithfulness to one’s nation and the Christian spirit, we face a lived reality which is laden with daily challenges, not to mention declarations and threats from certain movements. Where we note the rise of fundamentalism in many countries, we also witness the readiness of a great number of Muslims to resist this growing religious extremism.

71. As a consequence of this general situation, relations between Christians and Muslims are not always easy. Clearly, everything possible has to be done to improve and bring peace to the situation, whatever the difficulties. The initiative, usually undertaken by Christians, must be characterised by perseverance. These relations (which can grow towards dialogue) begin by being a good neighbour and can proceed to open collaboration by individuals or groups from the two religions. Centres of dialogue between Muslims and Christians, where they exist, are very useful, especially in periods of crisis. The Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue has an important role, in virtue of its status as an official entity of the Holy See.

72. Our schools and institutions have a very important role in these relations. They are open to everyone, Muslims and Christians alike, and provide the opportunity for better mutual understanding, overcoming specific prejudices and demonstrating more clearly the meaning of Christianity and being a Christian. Education about human rights and freedom of conscience, a part of religious and human formation in general, is vital for our societies and, consequently, must be developed.

73. Knowing one another is the basis of all dialogue. For this reason, a simple presentation of the Gospel and Christ, in local languages, based essentially on the New Testament and accessible to the mentality of the people who live in our societies, must be given as a matter of urgency and in collaboration with other Christians of the region. This would be of benefit to Christians and Muslims alike, in both our dialogue and our daily lives.

74. Today, the number of Christian and Muslim TV channels in Arabic and other languages is sufficient to provide any interested person with the means of knowing the other. The hope is for all Churches to work together in this endeavour. Maintaining objectivity in the information provided and being respectful of each other in dialogue is essential, if the grace of the Gospel is truly to be shared.

E. The Contribution of Christians to Society

1. Two Challenges for Our Countries

75. The challenges facing our countries today involve everyone – Christians, Jews and Muslims alike. In light of the military conflicts and interventions, the challenges of peace and violence occupy an important place. Speaking about and working for peace seems impossible, considering that war and violence are virtually forced upon us. The solution to conflicts rests in the hands of the stronger country in its occupying and inflicting wars on another country. Violence is in the hands of the strong and weak alike, the latter resorting to whatever violence is within reach in order to be free. Several of our countries (Palestine, Iraq) are experiencing war, and the whole region has suffered directly as a result. This situation, which has endured for generations, has been exploited by a most radical, global terrorism.

76. Too often, our countries identify Christianity with the West. While it is true that the West (Europe and America) has a Christian tradition and Christian roots, clearly, these countries today have secular regimes and governments and are far from being inspired in their politics by the Christian faith. This confusion, due to the Muslim world’s failing to make a distinction between politics and religion, seriously damages the Churches in our region. Indeed, the political choices of governments in the West are attributed to the Christian faith. It is important to explain what “secular” really means, and to remind people in our countries of the non-existence of a League of Christian States as compared to the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC).

77. In these circumstances, Christians can contribute by not only manifesting and living the values based on the Gospel, but also speaking the truth to the mighty, who oppress or follow policies contrary to the country’s best interests, and to those who meet oppression with violence. The pedagogy of peace is the most realistic path to follow, even though the majority of people might reject it. The likelihood of its being accepted is greatly increased, however, considering that, in the past, the violence of both the strong and the weak, has only led to failure and a general impasse in the region of the Middle East. Though indeed requiring a great deal of courage, our contribution is indispensable.

78. Modernity is an ambiguous reality. In one sense, it has an alluring aspect in promising comfort and well-being in the material things of life, even offering freedom from oppressive cultural or spiritual traditions. Likewise, modernity is the struggle for justice and fairness, the defence of the rights of the weakest, equality among all humans, men and women, believers and non-believers, etc. Generally speaking, it is the entire achievement of Human Rights, an immense step forward for humanity. In another sense, however, particularly for believing Muslims, the phenomenon is atheistic and immoral. They perceive it as a cultural invasion which threatens them and destroys their value system. They do not know how to react to it; indeed some fight it with all their might. Modernity attracts and repels at the same time. Our role in our schools and media is to form persons who are able to make a distinction between modernity’s positive and negative aspects, so as to conserve only what is best.

79. Modernity poses risks for Christians as well. Our societies are likewise threatened by the absence of a sense of God, atheism and materialism, and even more, relativism and indifferentism. We need to remind ourselves of God’s place in our personal lives and society, and to increasingly become a people of prayer and witnesses of the Spirit who builds and unites. These risks from modernity, like extremism, can easily destroy our families, our societies and our Churches. From this point of view, both Muslims and Christians share a common agenda.

2. Christians at the Service of Society in their Countries

80. We belong to the Middle East, exercise solidarity towards the region and are an essential part of it. As citizens, we share in every aspect of the responsibility of rebuilding and reversing the situation’s ill effects. Furthermore, this commitment is essentially ours as Christians, and, hence the dual obligation to share in the fight against the evils in our societies, whether political, legal, economic, social or moral in nature, and to contribute to building a society which is more just, more human, and more in solidarity with others.

81. In this regard, we follow in the footsteps of generations of Christians who have gone before us. Their contribution to society in education, culture and social works has been extensive and ongoing for many generations. They have exercised an essential role in the cultural, economic and political life of their countries. They have been pioneers in the Renaissance of the Arab nation.

82. With the exception of Lebanon, their presence today in civic life is more modest, principally because their number is reduced. Their role, however, is still recognised in society through the numerous institutions managed by the Churches and religious congregations, where the Church is present in society, a presence which is appreciated for the most part. The hope is that Christian lay-people will become more involved in society.

3. State-Church Relations

83. With the exception of Turkey, secularism not a part of Islam. Normally, Islam is the State religion. The principal source of legislation is Islam, inspired by Shariah law. For personal law (family and inheritance in some countries), there are particular regulations for Christian communities whose ecclesiastical tribunals are recognised and their decisions enacted. The constitutions of every country affirms the equality of citizens before the State. Religious education is compulsory in private and public schools, but is not always guaranteed for Christians.

84. Certain countries are Islamic States, where Shariah law is applied in both private and public life, including the lives of non-Muslims, which always constitutes discrimination and, therefore, a violation of a person’s human rights.

Religious freedom and freedom of conscience are foreign to a Muslim mentality, which recognises freedom of worship, but does not permit the profession of a religion other than Islam, still less the abandonment of Islam. With the rise of Islamism, incidents against Christians are increasing almost everywhere.

F. Conclusion: The Specific and Irreplaceable Contribution of the Christian

85. The specific, irreplaceable Christian contribution to the societies in which we live is to enrich them with the values of the Gospel. Christians are witnesses to Christ and the new values Christ has given humanity. For this reason, our catechesis needs to form people as believers and citizens, who perform their work in the different sectors of society. Political involvement devoid the values of the Gospel is a counter-witness, causing more harm than good. In more than one area, these values, especially human rights, coincide with those of Muslims. Consequently, there is much to be said for promoting these values in cooperation with one another.

86. Several conflicts in the Middle East have arisen as a result of the main point of global attention, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The Christian has a special contribution to make in the area of justice and peace. Our duty is to denounce violence courageously, no matter its source, and to seek a solution, something which can only be achieved through dialogue. Moreover, while demanding justice for the down-trodden, the message of reconciliation, based on mutual forgiveness, needs to be proclaimed. The power of the Holy Spirit enables us to forgive and to ask for forgiveness. This is the only path to creating a new humanity. Political powers need to be open to the spiritual aspects of people and situations, something which they can receive from humble, selfless Christian activity. Allowing the Holy Spirit to penetrate the hearts of men and women in our region, who are suffering from conflict situations, is a specific contribution which Christians can make and the best service they can offer to their society.

QUESTIONS

18. Does catechesis prepare the young to understand and live the faith?

19. Do homilies respond to the expectations of the faithful? Do they help them understand and live the faith?

20. Are Christian radio and TV programmes adequate? Would you like to see something else in your country? What programmes seem to you to be missing?

21. Practically speaking, how can ecumenical relations be promoted?

22. Does the re-discovery of a shared heritage (Syriac, Arabic and others) have some importance?

23. Do you think the liturgy needs to be reconsidered to some extent?

24. How can we bear witness to our Christian faith in our Middle Eastern countries?

25. How can relations with other Christians be improved?

26. How should we regard our relations with Judaism as a religion? How can peace and the end of political conflict be promoted?

27. In what areas can we collaborate with Muslims?

CONCLUSION

What is the Future for Middle Eastern Christians?

“Do not be afraid, little flock!”

A. What Lies Ahead for Middle Eastern Christians?

87. The reduced number of Christians in our region is a consequence of history. However, as a result of our actions as Christians, we can still improve the present and build for the future. Where, on the one hand, global politics will likely have an impact on a decision to stay in our countries or emigrate, on the other hand, accepting our vocation as Christians within and on behalf of our societies will be the paramount reason to remain and witness in our countries. At one and the same time, it is a question of politics and faith.

88. At present, this faith is fragile and perplexed. Our attitudes, including those of certain Pastors, vary between fear and discouragement. This faith must mature and grow more trustful. We must make a firm decision for the future, which will be shaped by how we manage to treat others and forge alliances with people of good will in our society. We need a faith which becomes involved in the life of society, a faith which serves to remind the Christians of the Middle East of the inspirational words: “Do not be afraid, little flock!” (Lk 12:32). You have a mission, you are to fulfill it and assist your Church and your country to grow and develop in peace, justice and equality for all citizens.

B. Hope

89. The hope which was born in the Holy Land has sustained peoples and individuals in trying times all over the world for over 2000 years. In the face of difficulties and challenges, that hope remains an inexhaustible source of faith, love and joy for the witnesses of the Risen Lord who is ever-present within the community of his disciples. In all our countries, this hope sustains us as we meditate on the words of Jesus: “Do not be afraid, little flock, for it is your Father’s good pleasure to give you the kingdom” (Lk 12:32).

90. Hope means, however, trusting in God and his Divine Providence, which watches over and guides the course of history for all peoples, and acting in union with God, as his “co-workers” (1 Cor 3:9), doing whatever is humanly possible to contribute to the developments now taking place. Our catechesis needs to give greater expanse to the limitlessness of God’s love for all; catechesis needs to form the faithful into true co-workers, under God’s grace, in every aspect of public life in our societies.

91. Abandoning ourselves to God’s Providence also means a deeper communion on our part, a greater detachment from an earthly point of view and more freedom from the thorns which stifle the word of God[16] and his grace in us. As St. Paul recommends: “Love one another with brotherly affection; outdo one another in showing honour. Never flag in zeal, be aglow with the Spirit, serve the Lord. Rejoice in your hope, be patient in tribulation, be constant in prayer.” (Rm 12:10-12). And Christ says to us: “if you have faith as a grain of mustard seed, you will say to this mountain, ‘Move from here to there,’ and it will move; and nothing will be impossible to you” (Mt 17:20; cf. Mt 21:21).

92. Such is the nature of belief needed for our “fathers and heads” and the faithful alike. May the Virgin Mary, present with the apostles at Pentecost, help us to be men and women ready to receive the Spirit and to act with his power.

QUESTIONS

28. Why are we afraid of the future?

29. How do we incarnate our faith in our work?

30. How do we incarnate our faith in politics and society?

31. Do we believe we have a specific vocation in the Middle East?

32. Any other comments?

— — —

[1] Cf. BENEDICT XVI, Discourse to the Congregation for Eastern Churches (9 June 2007): L’Osservatore Romano: Weekly Edition in English, 27 June 2007, p. 3.

[2] COUNCIL OF CATHOLIC PATRIARCHS OF THE MIDDLE EAST, 10th Pastoral Letter on Arab Christians Facing Today’s Challenges: “God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit which has been given to us” (Rm 5:5), General Secretariat, Bkerké, 2009, § 13 ff.

[3] Ibid., § 7.

[4] Cf. COUNCIL OF CATHOLIC PATRIARCHS OF THE MIDDLE EAST, 4th Pastoral Letter on the Mystery of the Church: “I am the vine, you are the branches” (Jn 15:5), General Secretariat, Bkerké, 1996, § 5-16.

[5] Cf. COUNCIL OF CATHOLIC PATRIARCHS OF THE MIDDLE EAST, 10th Pastoral Letter on Arab Christians Facing Today’s Challenges: “God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit which has been given to us” (Rm 5:5), General Secretariat, Bkerké, 2009, § 11.

[6] Saint Paul refers twice to the “Church of God which is at Corinth” (cf. 1 Cor 1:1 and 2 Cor 1:2)

[7] Cf. Mc 10, 35-37. In Mt 20, 20-21, their mother addressed this question to Jesus.

[8] Cf. SECOND VATICAN ECUMENICAL COUNCIL, Decree on Ecumenism Unitatis redintegratio, 3; 22.

[9] In these two Holy Places, the status quo governs relations between the three confessions which are joint owners: the Latins (represented by the Custodians of the Holy Land or the Franciscan Fathers), the Armenians and the Greeks. Occasionally, differences or scandals arise which are immediately exaggerated by the media to the great harm of the Church.

[10] 5 Orthodox Churches, 6 Catholic Churches and 2 Protestant communities.

[11] COUNCIL OF CATHOLIC PATRIARCHS OF THE MIDDLE EAST, 10th Pastoral Letter on Arab Christians Facing Today’s Challenges: “God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit which has been given to us” (Rm 5:5), General Secretariat, Bkerké, 2009, 27.

[12] BENEDICT XVI, Apostolic Visit to the Holy Land, Welcoming Ceremony in Bethlehem (13 May 2009): L’Osservatore Romano: Weekly Edition in English, 20 May 2009, p. 11.

[13] BENEDICT XVI, Apostolic Visit to the Holy Land, Discourse at Ben Gurion Airport in Tel Aviv (11 May 2009): L’Osservatore Romano: Weekly Edition in English, 20 May 2009, p. 3.

[14] JOHN PAUL II, Message for the World Day of Peace (1 January 2002): AAS 94 (2002) 132-140.

[15] SECOND VATICAN ECUMENICAL COUNCIL, Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions Nostra Aetate, 3.

[16] Cf. The Parable of the Sower, for example, in Mt 13:7 and parallel passages.

* * *

© The General Secretariat of the Synod of Bishops and Libreria Editrice Vaticana.