Experts in Assyriology — who specialize in the archaeological, historical, cultural and linguistic study of Assyria and the rest of ancient Mesopotamia (Iraq) –spend many years painstakingly trying to understand Akkadian texts written in cuneiform, one of the oldest forms of writing known.

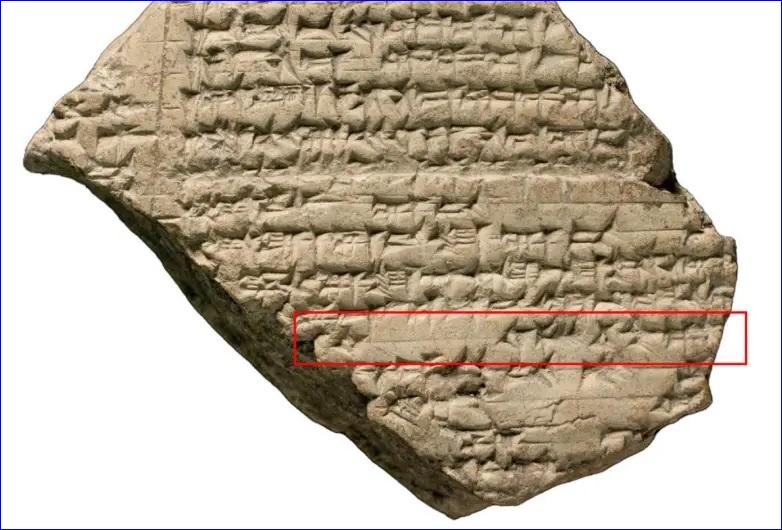

Cuneiform is translated as “wedge-shaped” because in ancient times, people wrote it using a reed stylus cut to make a wedge-shaped mark on a clay tablet.

But now, researchers at Tel Aviv University (TAU) and Ariel University have developed an artificial intelligence model that will save all this effort. The AI model can automatically translate Akkadian text written in cuneiform into English.

Who were the ancient Assyrians?

In 721 BC, Assyria swept out of the North, captured the Northern Kingdom of Israel and took the Ten Tribes into captivity, after which they became lost to history. Assyria, named for the god Ashur (highest in the pantheon of Assyrian gods), was located in the Mesopotamian plain. Historians note that Assyrian Jews first appeared in that region when the Israelites were exiled there, and they lived continuously alongside the Assyrian people in the territories after the Assyrian exile.

Hundreds of thousands of clay tablets from ancient Mesopotamia, written in cuneiform and dating back as far as 3,400 BC have been found by archeologists — far more than could easily be translated by the limited number of experts who can read them.

Dr. Shai Gordin of Ariel University and Dr. Gai Gutherz, Dr. Jonathan Berant and Dr. Omer Levy of TAU and colleagues have just published their findings in the journal PNAS Nexus under the title “Translating Akkadian to English with neural machine translation.”

When they developed the new machine-learning model, they trained two versions — one that translates the Akkadian from representations of the cuneiform signs in Latin script and another that translates from unicode representations of the cuneiform signs. The first version, using Latin transliteration, gave more satisfactory results in this study, achieving a score of 37.47 in the Best Bilingual Evaluation Understudy 4 (BLEU4), which is a test of the level of correspondence between machine and human translation of the same text.

The program is most effective when translating sentences of 118 or fewer characters. In some of the sentences, the program produced “hallucinations” — output that was syntactically correct in English but not accurate.

Gordin noted that in most cases, the translation would be usable as a first-pass at the text. The authors propose that machine translation can be used as part of a “human-machine collaboration,” in which human scholars correct and refine the models’ output.

Hundreds of thousands of clay tablets inscribed in the cuneiform script document the political, social, economic and scientific history of ancient Mesopotamia, they wrote. “Yet, most of these documents remain untranslated and inaccessible due to their sheer number and the limited quantity of experts able to read them.”

They concluded that translation is a fundamental human activity, with a long scholarly history since the beginning of writing. “It can be a complex process, since it commonly requires not only expert knowledge of two different languages but also different cultural milieus. Digital tools that can assist with translation are becoming more ubiquitous every year, tied to advances in fields like optical character recognition (OCR) and machine translation. Ancient languages, however, still pose a towering problem in this regard. Their reading and comprehension require knowledge of a long-dead linguistic community, and moreover, the texts themselves can also be very fragmentary.”