Reaching the source of the Tigris is not an easy task. Where a dirt road ends, a small path leads over the shoulder of a jagged mountain whose peaks are gnawed like fingernails. The path becomes a goat track, treacherously narrow, winding around the hillside until it is halted by a tumble of springs. These form a torrential stream that disappears into a vast, arched tunnel. When the nascent river emerges 1.5km later, it is tamed by whatever happened deep inside the cave.

The ancient Assyrians believed this to be a place where the physical and spiritual worlds collide. Three thousand years ago, their armies travelled upstream to offer sacrifices. A relief of Tiglath-Pileser, King of Assyria from 1114-1076 BCE still stands at the mouth of the tunnel. Time has dulled his edges, but he remains upright and regal, pointing out across his empire.

The source of the Tigris lies in present-day Turkey, where it flows south-east out of the Taurus Mountains. It skims a pinched corner of north-east Syria and then passes through the cities of Mosul, Tikrit and Samarra on its way to Baghdad. In southern Iraq, the sprawling Mesopotamian Marshes absorb the Tigris close to the confluence with its sister river, the Euphrates, and both flow together to the Persian Gulf.

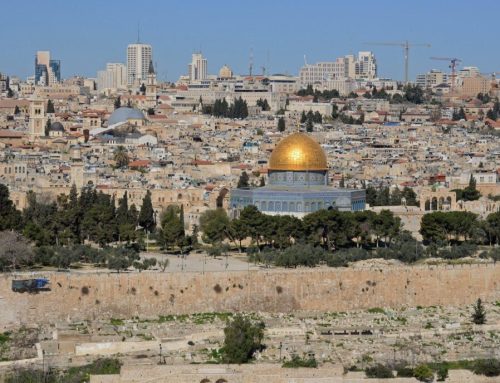

Around 8,000 years ago, our hunter-gatherer ancestors settled in the great floodplain between these two rivers and developed agriculture and animal husbandry, leading many to call the area the “Cradle of Civilisation”. From these early city-states — like Eridu, Ur and Uruk — came the invention of the wheel and the written word. Codified legal systems, sailing boats, beer brewing and love songs followed, among other inventions.

And yet, because of the decades of conflict that have plagued modern Iraq, the fact that the Tigris has guarded and shaped our shared human heritage is easily forgotten.

For 10 weeks in 2021, a small team and I travelled roughly 2,000km by boat and overland from the Tigris’ source to where it empties into the Persian Gulf — a journey one advisor told me likely hadn’t been attempted since the Ottoman era. My goal was to chart the river’s historical importance and tell its story through the voices of those who live along its banks, while also investigating the threats to its future. A combination of geo-political instability, poor water management and climate change has led some to state that this once-mighty river is dying. I hoped our journey would be a reminder of what emerged from this land, and what we would collectively lose if the river that birthed civilisation dried up.

Eighty kilometres from the Tigris’ source in Eğil, Turkey, the ramparts of an Assyrian castle have been modified by the Greeks, Armenians, Byzantines, Romans and Ottomans who all later settled along the river’s banks. Further downstream in Diyarbakır, Turkey, where another fortress still stands that has existed in some incarnation since the Bronze Age, a similar layering has taken place. Today, the city is the de-facto capital of Turkey’s large Kurdish population, and in its labyrinthine alleyways, we rested in a basalt courtyard under the shade of a mulberry tree, transfixed by the haunting sounds echoing around the walls.

There, a woman in a quilted beige jacket sat on a bench, her right hand cupped around her ear. Her name was Feleknaz Aslan, and for 30 minutes, her booming voice held us captive. She was a dengbêj, a Kurdish singing storyteller, whose ancestors have passed histories and folktales down through generations. Aslan’s song was about a doomed love affair on the banks of the Tigris. Most dengbêj are men now, she said, but the practice was invented by women. It was a way of preserving identity and culture, and she explained that the Tigris is a common backdrop in these songs — recognised then as now as a central feature of life for Kurds in this region.

South-east of Diyarbakır, the Tigris etches a deep canyon through the Tur Abdin region of Turkey’s Taurus mountains. For centuries, this has been the heartland of the ancient Syriac Orthodox Church, whose origins date back to the dawn of Christianity. We climbed to a remote 4th-Century monastery, Mor Evgin, which clings to the cliff as if suspended by faith alone.

Inside the nave, plaster applied by some of the world’s first Christians still stuck to the walls, and spidery Syriac script crawled around the walls in webs of prayer. I lit a candle in an alcove and bowed my head. It was another reminder of how the Tigris’ fertile watershed allowed Judaism, Christianity and Islam to flourish (Abraham, a spiritual model for each faith, is said to have come from here), and how these populations later took their goods, ideas, beliefs to the far corners of the world.

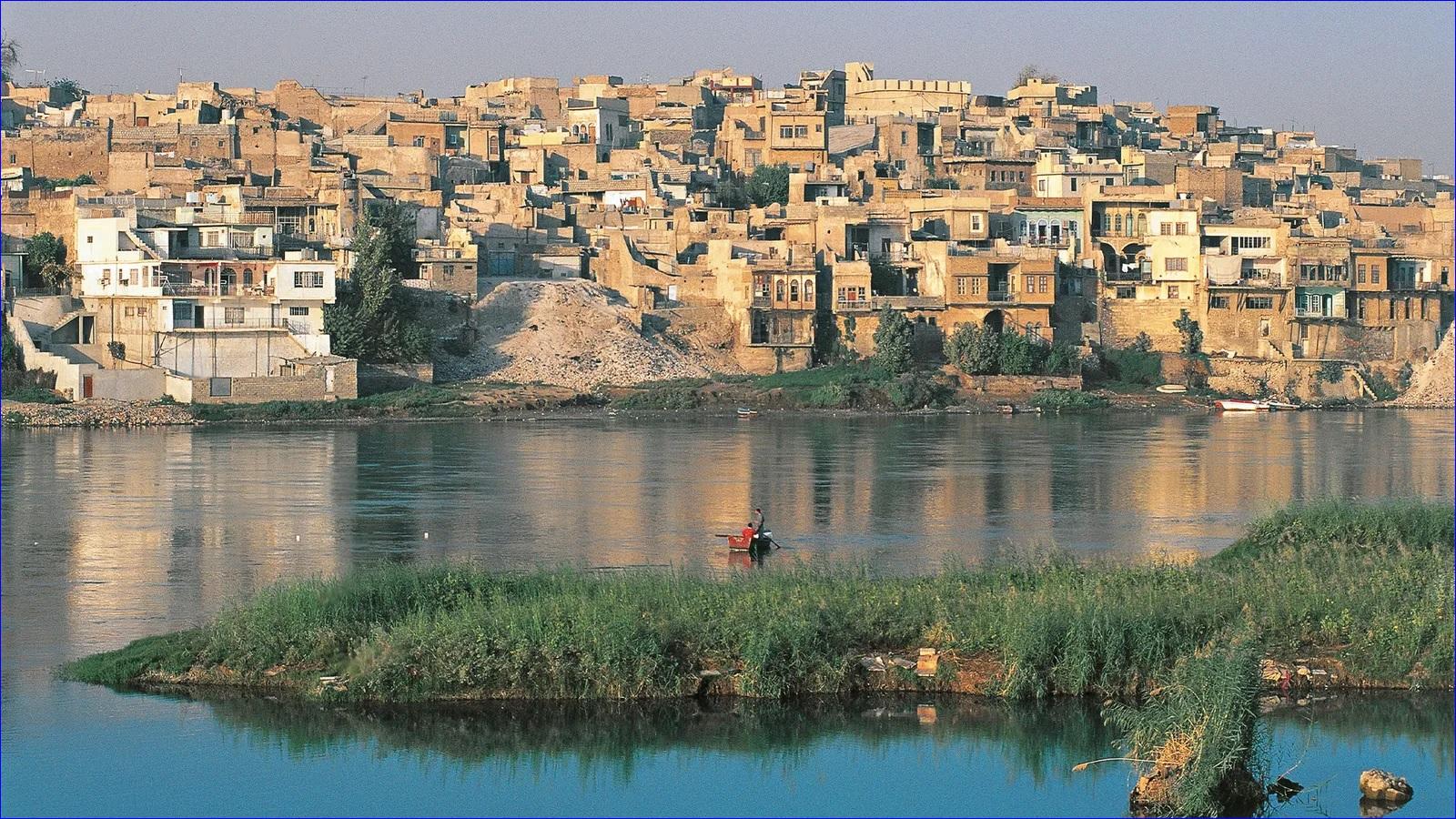

We travelled by small boat whenever possible, though access to the Tigris is often tricky. In Turkey, navigating the river is difficult because of a series of highly contentious dam-building projects. In Syria, the Tigris is an international border. It wasn’t until Mosul, a city carved in two by the river, that we were finally able to travel more freely.

When ISIS occupied Mosul from 2014-2017, it forbade residents from using the Tigris and Mosul’s Old City on the river’s west bank became the group’s last refuge.

During the fighting, every bridge in Mosul spanning the river was destroyed and some jihadists reportedly jumped into the Tigris in an attempt to escape during the final battle. Historically, the river might have been a connective force, but we saw how it became a point of conflict.

Mosul’s Arabic name, Al-Mawsiil, means “the linking point”, likely because it was a crossroads of trade and a major hub along the Tigris between Diyarbakır and Basra. Established in the 7th Century BCE, it’s one of the oldest cities in the world, and during its pinnacle in the 12th-Century AD, it not only wielded great power and influence over the region but became ethnically and religiously diverse. This confluence of cultures created a rich cultural space, and while much of the Old City was destroyed by ISIS, the city’s spirit lingers on.

“People think we have nothing left,” said Salman Khairalla, who co-founded the Tigris River Protectors’ Association and a companion on our journey. “But there’s so much along the Tigris that survived it all. And more than that, we Iraqis always rebuild. We will never accept destruction.”

In Mosul, the toppled 12th-Century Great Mosque of al-Nouri is being reconstructed with a huge endowment from Unesco and the UAE. Just as striking is the community-led cultural revival. Opposite al-Nuri is Baytna, meaning “our home”, where young Moslawi artists have created a multi-purpose museum, cafe and venue space by refurbishing an old Ottoman home. “We don’t want people to forget what happened here,” Sara Salem Al-Dabbagh, one of the space’s founders, told me. “But we want to create opportunities for employment, and a place to support people with skills.”

The Tigris carried us on to Ashur, the first capital of the Assyrian empire, where a 4,000-year-old ziggurat looms over the river. In the desert beyond were Nimrud, a later Assyrian capital and the 2,000-year-old caravan city of Hatra. All three were damaged by ISIS, but heroic teams of local archaeologists are doing their best to protect the sites, even with the scant resources available.

In a region that often makes international news for its war and hostility, one of the most lasting impressions of my journey was that of unadulterated hospitality. Even during Ramadan, tea was prepared by hosts who were themselves fasting. Many a poor goat ended up atop a rice platter for us in lavish banquets. In the village of Kifrij, the mayor told us how two young shepherds smuggled civilians across the Tigris from ISIS-held territory to safety at night using only a tractor inner tube. I found that no amount of recent violence could shatter residents’ willingness to help strangers and their sense of generosity. Like strands of the braided river itself, the Tigris is woven throughout all of these stories; as a boundary between life and death, but also as the vehicle for great acts of kindness.

We spent a Sunday with the Mandaeans, the smallest, and perhaps oldest, ethno-religious group in Iraq. The Mandaeans believe in regular baptisms as a source of spiritual nourishment and a way to cleanse sins. Baptisms must be performed in running water and the Tigris, as one of the two rivers that allowed the faith to first flourish, is still home to many members of the community.

I watched as, one by one, a priest led eight women to the Tigris and gently submerged them, whispering prayers in Mandaic; an ancient Aramaic dialect for which they are the sole guardians. “The water here is the same as in the next universe,” the priest’s assistant told me.

The river that the Mandaeans and so many communities rely on is in danger. But from activists like Khairalla to the archaeologists of Ashur to the Moslawi artists reclaiming their culture, I found that the Tigris’ guardians are not willing to give up and are committed to rebuilding.

When I asked Khairalla about the future of the river, he said simply, “Iraqis must always have hope. Whatever generations before us do, we can change.”

By BBC