Since a week the recurrent hope that the siege of the Church of Nativity and the curfew would be lifted, is dashed each time, but on Friday a real end comes to the almost six-week long affair. Mary and Janet are glued to the Al Jazeera satellite station, based in Qatar but with correspondents located in the major Palestinian towns. Even the local TV largely copies Al-Jazeera. Due to the closure, the Bethlehemites have become completely dependent upon the TV for getting news about the Church.

Since a week the recurrent hope that the siege of the Church of Nativity and the curfew would be lifted, is dashed each time, but on Friday a real end comes to the almost six-week long affair. Mary and Janet are glued to the Al Jazeera satellite station, based in Qatar but with correspondents located in the major Palestinian towns. Even the local TV largely copies Al-Jazeera. Due to the closure, the Bethlehemites have become completely dependent upon the TV for getting news about the Church.

In Bethlehem it is Guevara al-Budeiri who reports almost every hour. She talks with fury in her eyes, restraining herself within an objective vocabulary but always concluding her report with: “This is Guevara al-Budeiri, Church of Nativity, Occupied Bethlehem,” emphasizing “occupied.” Guevara and her colleague in Ramallah, Shireen Abu Akleh, seem to be role models for the youth. Mary hears our neighbours’ kids talking admiringly about them. Jara points with her finger on the screen to spot Tony Salman, Mary’s cousin, who lost eleven kilos as he stayed in the church during the siege as a liaison between the priests and the militants.

* * *

The denouement is somehow an anti-climax since most Bethlehemites, though relieved to leave their houses, are not very happy about the compromise reached. As a visiting acquaintance says, “How can you insist upon the Palestinian right to return while at the same time agreeing with deportation, which is exactly the opposite?” Mary, too, feels a combination of relief and sadness, and she gets tears in her eyes when she sees the militants who come out of the church waving from a distance to their family members whom they cannot say good by normally. The group who arrives in Gaza is interviewed by Palestine TV; Mary knows some of the men, who almost look like kids; one of them is a former student. In the studio, they are called and greeted by their loved ones, whom they will likely not meet for many years. One of them says that he for the first time sees the sea. In fact, many young people in the West Bank have never had a chance to go out of the area.

Mary cannot understand that they are called ‘terrorists’. “They all do this to defend their homeland. What did they do in Holland when you were occupied? Did you not have terrorists?” Our visiting neighbour tells a story which is quite familiar here: “Imagine you put a cat in a house and you close him up for a week. Do you know what he will do when you open the door? He will attack and scratch you violently.” The anger does not decrease with another piece of distressing news: Israel wants to bring over Jews from Peru in order to put them in a settlement close to Bethlehem.

* * *

In the evening I go with Jara to the Nativity Square. During the past weeks we did not recognize our streets with their broken lantern posts, tanks, armoured personnel carriers, taxis and cars with tapes attached forming the letters ‘TV’, ambulances, a group of Buddhist monks slowly beating drums, and kids, joined by Jara, who imitate the sounds of the jeep’s loudspeakers ‘mamnou’a el-tajawoul’ (forbidden to go out). A few days ago I myself was watched on the street by people while pushing a small carrier with Red Cross food – a bit of riyaade (sports) was good for me, it was said. At the distribution place one woman told that she never thought she would once accept an aid box; but after so many weeks she was not ashamed anymore. Another emphatically said that his daughter had helped many others, but now they also had to think about themselves. A palpable sense of embarrassment caused by its very denial. Mary commented that in case there would not have been enough for others, she would have refused, since we still had money at home. But we ran out of bread and a neighbour showed us how to make her delicious fresh bread from the Turkish dough that was part of the aid package.

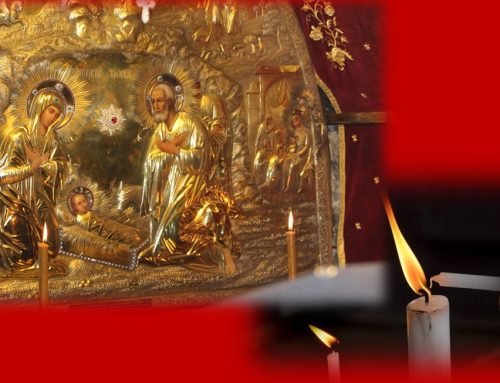

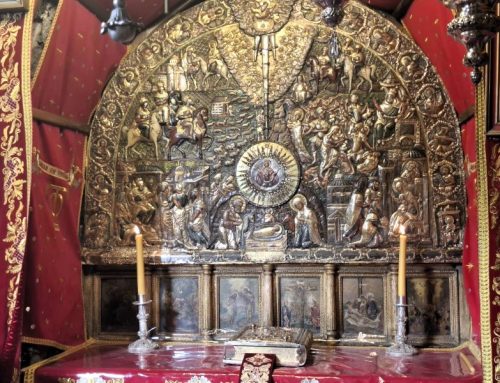

But it is all over now. With Jara on my shoulder, I walk along the dark streets – no street electricity these days – and watch the shadows of destruction and dirt. The people enter hesitatingly the streets, there is even music from a CD shop, and I shake hands with colleagues and acquaintances on the street: the Brothers of the University, who also want to take stock of the situation; Fuad and Elias, who shows me the bullets around the small door of ‘humility’ in the Nativity Church, and bystanders with whom I talk just to reclaim public space. I give Jara the mobile which she uses from her high vantage point to describe to Janet the destruction around, especially the Peace Center next to the Church. She might become a journalist, too. Later on we hear that all computers and printers in the Peace Center have been taken away, and photocopiers destroyed, just like that.

* * *

On Saturday, it is still difficult to get into a normal rhythm. The government and UNRWA schools open; Jara’s Freres School decides first to bring all teachers together to assess the situation. Even my family and family in law do not go out except for necessities. We do not yet feel a sense of freedom. In the garden Jara and I play the figures of fairy tales: the wolf, the monster, and the witch. In the modern, educationally responsible Dutch books we read that those traditional baddies have their good sides; the bad wolf turns out to be likable, and the monster can be afraid. I wonder how Jara and Tamer, as they grow up, will relate to that more reality-based category of ‘baddies’ they know or will learn to know – the Israelis. We eagerly like to see them becoming more human, too.