But the meeting’s not in the actual village of Karamlesh. It’s 40 miles away in the northern Iraqi city of Erbil, on red plastic chairs under a dust-yellow sky, next to the corrugated trailers some of these people have been living in since 2014 when the Islamic State took their village.

Karamlesh is one of a cluster of Christian villages nestled in the Nineveh plain, in northern Iraq near Mosul. Some of the oldest churches and monasteries in the world are there.

A little over two years ago, ISIS poured into those villages and the people fled. Now, as Iraqi forces backed by the U.S.-led coalition press an offensive against ISIS in Mosul, ISIS fighters have been pushed from the villages.

So, the people of Karamlesh gathered to discuss what to do now. At the front of the meeting stood a stark metal cross with a white ribbon on it and a black one.

With a flourish, the priest, Boulos Thabet Habib, removed the black ribbon, celebrating the liberation. Applause broke out, and smiles.

Then, Habib began to speak. He sketched out a bright future for the village, outlining plans for repairing the houses damaged by fighting, filling in ISIS tunnels.

But people seemed torn. After the meeting, Maha al Kahwaji, a woman with bright red hair, became animated as she spoke about Karamlesh.

“I adore my village. I adore it,” she said. As ISIS approached, she insisted on staying in the church, and refused to leave initially.

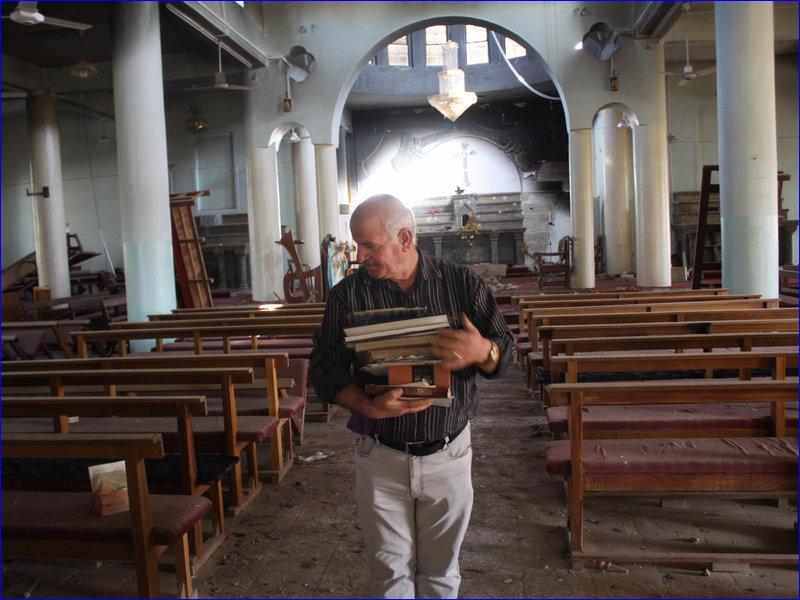

Karamlesh was held by ISIS for more than two years. The militants dug tunnels and filled shops and houses with explosives. ( Alice Fordham/NPR)

Eventually she was forced to flee, and has been living in Erbil more than two years, longing for home.

“But to return is difficult,” she said. “It’s not just difficult, with the tunnels, the burning of homes and the destruction, it’s impossible.”

The priest may say lovely things; he dreams and we all dream too, she explained. But she is unconvinced the plan is anything more than a dream. She wants to go back, but every week a family from Karamlesh leaves Iraq, seeking asylum elsewhere, she said.

Her dilemma is shared by tens of thousands of people — Christians and other minorities — targeted and displaced by ISIS.

They are happy the group’s brutal stranglehold is over, but are put off going home by the destruction of their homes, a mistrust of Iraq’s security forces and a fear that the Sunni Muslims in their area collaborated with ISIS.

One businessman from Karamlesh, Taher Bahoo, is determined to return the village to life.

We went there together, turning off the road to Mosul a few miles before the front line, explaining to the Iraqi army soldiers at the checkpoints that we were with a resident of the village.

The difference from the village I saw on an earlier visit, in 2014, before ISIS wrought their havoc, was striking. In front of the first church, at the entrance to the town, were singed patches of earth where a flower garden used to be. A soldier’s uniform was drying on an improvised washing line. Another was being laundered in the baptismal font.

Bahoo led the way into the church building, pointing out numerous tunnels ISIS had built — well over six feet high. Some of them are so long no one is quite sure where they end up. One slopes uphill and comes out at a viewpoint used by a sniper.

Bahoo looked out from the viewpoint over the village at charred wrecks of houses and cars, streets full of shrapnel. The only people visible are the security forces.

“When I was just 5, 6, 7 years age, we were playing here,” he said. “It was peaceful. It’s difficult – very difficult – to imagine what happened here.”

Going further into the village, Bahoo and I walked past little stores full of remnants of explosives, ancient graveyards and monasteries that are damaged or destroyed.

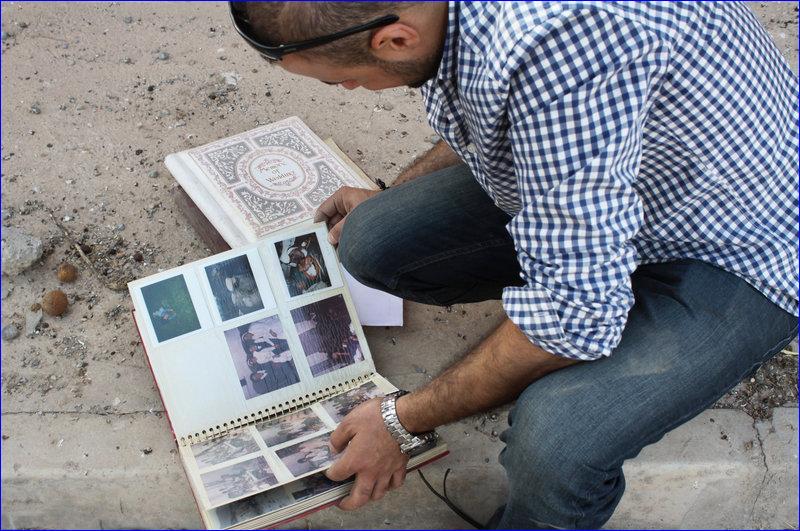

Businessman Taher Bahoo lingers over family photo albums he salvaged from his home, which was ransacked by ISIS. ( Alice Fordham/NPR)

“Looks like, I don’t know — another place,” he said quietly.

This destruction is the first obstacle for those trying to persuade Christians to come back. But the only other civilian we met, teacher Khalid Yaako Touma, salvaging family photos from his ruined house, said other factors were also important.

“This is all the fault of the government,” he said. On the day ISIS came to Karamlesh, the Iraqi army and the ethnic Kurdish Iraqi forces known as peshmerga both melted away, he said.

A lot of villagers also say that they’re frightened of Muslims who live in the area. They believe, although it’s not at all accurate, that those Muslims all joined ISIS.

In another mainly Christian village close by, Qaraqosh, a retired army general, Behnam Abbush, said he believed he has an answer to this fear.

“They must put the security in the hand of the people of this land — that’s what I want,” said the white-haired man. He leads a Christian militia called the Nineveh Protection Units, currently working alongside the Iraqi army but pushing to be the holding force here.

He thinks Christians will come back to these villages if they know their own people are keeping them safe. His group claims to have thousands of men ready for the task.

As he spoke, an elderly shepherd with about a dozen sheep walked down the abandoned street.

“Who is he? Where’s he from?” the general shouted to his men.

They stopped the shepherd for questions and Behnam said Muslims shouldn’t even walk through the streets here for the moment.

“Because this is Christian village, 95 percent this is Christian,” he said.

In Karamlesh, the businessman, Bahoo took a detour into his family house.

“All my life I was here,” he murmured as we rounded the corner. The orange and olive trees in the garden are overgrown, and the house is ransacked. But it is salvageable. He doesn’t want his parents to see it yet.

“It’s better to keep them far away until we just clean everything and repair everything,” he said.

He went inside to dig out the family photo albums from the mess ISIS left behind, leafed through pictures of his father in military uniform in the 1960s, family holidays, first holy communion.

One album, meant for wedding pictures, has a little music box built in. It played the wedding march, tinkly and sweet, as Bahoo sat on the sidewalk, deep in the memories, oblivious for a moment to the scorched devastation of the deserted little village.

Source: Aina.org